I’ve been following pretty closely the response to the pepper spraying at UC Davis, and I’ve been hoping to find time to blog about it. Unfortunately, between grant writing and grant reviewing and end-of-semester craziness, I haven’t had time to share or comment on the 75 or so tabs I have open in Firefox at the moment. Those tabs are really beginning to slow down my laptop, so I thought I’d clear out some of them by sharing some of the more interesting tidbits.

Close readings

Lambert Strether offers a play-by-play description and transcription of the most popularized video of the incident.

Lili Loufbourow undertakes a close reading of one of the videos of the pepper spraying. Here’s an excerpt:

It’s transcendently brilliant, this tactic–the students offer an alternative in a high-pressure situation, a situation that no one wants, but which seems inevitable in the heat of the moment. It’s an act of mercy which, like all acts of mercy, is entirely undeserved. Watch the other officers’ surprise at this turn in the students’ rhetoric, after they had (rightfully) been chanting “Shame on you!” Watch the officers seriously consider (and eventually accept) the students’ offer.

As the officer in the left foreground teeters back and forth, nervous, braced, thinking, watch the power-drunk cop on the right (who I think is the one who pepper-sprayed the crowd earlier) brandish not one but TWO bottles of pepper-spray, shaking them, not just in preparation, but in anticipation. He’s seconds away from spraying the students again. His mask is up, you can see his face, but it’s a nonexperience: it’s blank, immobile. It would be inaccurate to say that he’s immune to the students’ appeal; he’s not even bothering to listen. All he hears are sounds. No signals, all noise.

Megan Garber suggests that the image of the pepper-spraying cop could change the trajectory of the Occupy movement:

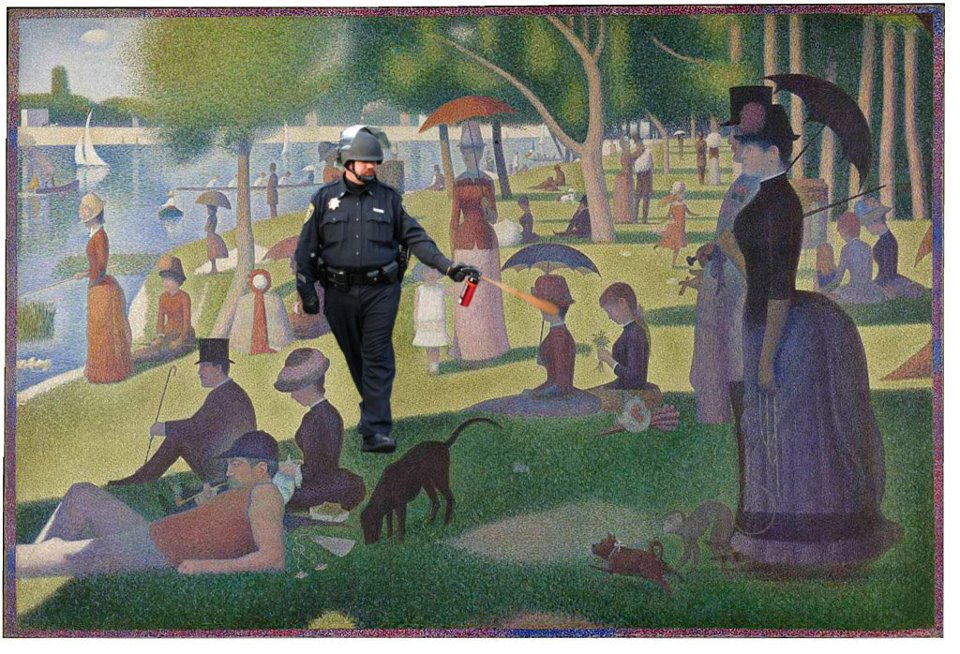

The image itself, I think — as a singular artifact that took different shapes — contributed to that transition, in large part because the photo’s narrative is built into its imagery. It depicts not just a scene, but a story. It requires of viewers very little background knowledge; even more significantly, it requires of them very few political convictions, save for the blanket assumption that justice, somehow, means fairness. The human drama the photo lays bare — the powerless being exploited by the powerful — has a universality that makes its particularities (geographical location, political context) all but irrelevant. There’s video of the scene, too, and it is horrific in its own way — but it’s the still image, so easily readable, so easily Photoshoppable, that’s become the overnight icon. It’s the image that offers, in trending topic terms, a spike — a rupture, an irregularity, a breach of normalcy. It’s the image that demands, in trending topic terms, attention.

And it also demands participation.

Hence we have an entire blog devoted to the meme of the Pepper-Spraying Cop. Here’s a sample image:

(Speaking of memes, check out the reviews on a pepper-spray canister at Amazon. This one is my favorite.)

(Speaking of memes, check out the reviews on a pepper-spray canister at Amazon. This one is my favorite.)

Gen Y on Occupy UC Davis

BoingBoing has an interview with one of the students who was pepper sprayed. The student provides a concise summary of what the students are protesting at Davis:

We’d been protesting at UC Davis for the last week. On Tuesday there was a rally organized by some faculty members in response to the brutality on the UC Berkeley campus, and in response to the proposed 81% tuition hike.

One of the reasons I am involved with #OWS, and advocating for an occupy movement on the UC campus, is to fight privatization and austerity in the UC system, and fight rising tuition costs. I think that citizens have the right to get an education regardless of economic condition. Most people are not going to get a job where they can afford to pay off student loans. But to exclude people from knowledge is unconscionable.

Zack Whittaker comments on UC Davis Police Chief Annette Spicuzza’s explanation for the pepper spraying—“Officers were forced to use pepper spray when students surrounded them. . .There was no way out of the circle.” Yet everyone who had seen the videos of the pepper spraying could see that Lt. John Pike stepped over the protestors to spray them in the face. Whittaker uses this failure of police department and university spin as emblematic of the new era of citizen journalism. While I hesitate to call most of the witness-created media from the UC Davis protest “citizen journalism”—much as I’m loath to call this round-up of UC Davis links “curation”—Whittaker does have a point about how Generation Y experiences flashpoints:

What we see in any modern event, no matter how off the cuff or sporadic, is a sea of cameras. One report likened it to a panopticon society.

It is not 911 or 999 we call in an emergency. We do not think to engage with the situation. But what we do, as the Generation Y, is pull out our phones and start recording; documenting every second of the event for history’s benefit.

Responses from UC Davis faculty

As far as I know, the first letter-length response from a faculty member at UC Davis came from Nathan Brown, an assistant professor in the English department, who called for UC Davis Chancellor Linda Katehi’s resignation.

Because it’s been well publicized, if you’ve been following this event at all, you’ve probably already seen music and technocultural studies professor Bob Ostertag’s editorial on the militarization of campus police. (I was Bob’s TA when I started the original Clutter Museum, and if you ever have a chance to hear him speak, I recommend you seize it.) I want to highlight a couple of passages. First, Ostertag considers the use of pepper spray as both a health concern and disciplinary measure:

I just spoke with a doctor who works for the California Department of Corrections, who participated in a recent review of the medical literature on pepper spray for the CDC. They concluded that the medical consequences of pepper spray are poorly understood but involve serious health risk. As with chili peppers, some people tolerate pepper spray well, while others have extreme reactions. It is not known why this is the case. As a result, if a doctor sees pepper spray used in a prison, he or she is required to file a written report. And regulations prohibit the use of pepper spray on inmates in all circumstances other than the immediate threat of violence. If a prisoner is seated, by definition the use of pepper spray is prohibited. Any prison guard who used pepper spray on a seated prisoner would face immediate disciplinary review for the use of excessive force. Even in the case of a prison riot in which inmates use extreme violence, once a prisoner sits down he or she is not considered to be an imminent threat. And if prison guards go into a situation where the use of pepper spray is considered likely, they are required to have medical personnel nearby to treat the victims of the chemical agent.

(How hot is the pepper spray UC Davis police used? Check out Deborah Blum’s post for the science of pepper spray.)

Ostertag also provides, very briefly, a history of linked arms in civil rights protests in the United States. He then explains how the meaning of linked arms has shifted:

Throughout my life I have seen, and sometimes participated in, peaceful civil disobedience in which sitting and linking arms was understood by citizens as a posture that indicates, in the clearest possible way available, protestors’ intent to be non-violent. . . . Likewise, for over 30 years I have seen police universally understand this gesture. . . .

No more.

The UC Davis English department is calling for the resignation of UC Davis Chancellor Linda Katehi—on the department’s home page. The department also asks for the disbanding of the University of California police department. The Physics faculty also has released a letter calling for Katehi’s resignation.

Professor Emeritus Jon Wagner offers a flyer for “UCD Omni-Spray: A Broad Spectrum Democraticide” (PDF).

Cynthia Carter Ching has issued an apology to students and encouraged her fellow faculty to recommit themselves to administrivia, even though such work is neither interesting nor fulfilling:

And in many cases that power wasn’t just taken from us, we gave it away, all too gladly.

You know, it wasn’t malicious. We thought it would be fine, better even. We’d handle the teaching and the research, and we’d have administrators in charge of administrative things. But it’s not fine. It’s so completely not fine. There’s a sickening sort of clarity that comes from seeing, on the chemically burned faces of our students, how obviously it’s not fine.

So, to all of you, my students, I’m so sorry. I’m sorry we didn’t protect you. And I’m sorry we left the wrong people in charge.

On the Monday following the Friday pepper spraying, the UC Davis community held a rally that attracted a couple thousand people (pic). The Sacramento Bee covered the events, and the Davis Enterprise reported on faculty who participated in the rally.

This week, UC Davis faculty are offering classes in a week-long teach-in. Were I still at UC Davis, I’d definitely be attending several of them.

Yudof has appointed former Los Angeles Police Department Chief William Bratton to lead the investigation of the pepper spraying incident. The women and gender studies faculty at UC Davis has launched a petition protesting that decision, with a very thorough and, I think, convincing explanation of why Bratton is not a good choice in this case. You can read their letter, and sign the petition if you’d like, at Change.org.

The bigger context

Kate Bowles at Music for Deckchairs suggests we need to look beyond Lt. Pike and investigate instead the forces that allowed his actions to emerge:

The world’s attention has been focused on the face and demeanour (and now the salary) of Officer Pike, wielding the pepper spray like a bug gun, but what brought each of his colleagues to that point where their collective and individual efforts in that awful situation felt appropriate, inevitable, even wise? How did each of them get caught up in this profound miscalculation, suddenly and so decisively on the wrong side of our global, chanting crowd?

Several columnists at The Atlantic chimed in as well. Alexis Madrigal picked up on Bowles’s theme with her post “Why I Feel Bad for the Pepper-Spraying Policeman, Lt. John Pike”:

Structures, in the sociological sense, constrain human agency. And for that reason, I see John Pike as a casualty of the system, too. Our police forces have enshrined a paradigm of protest policing that turns local cops into paramilitary forces. Let’s not pretend that Pike is an independent bad actor. Too many incidents around the country attest to the widespread deployment of these tactics. If we vilify Pike, we let the institutions off way too easy.

James Fallows considers the moral power of images emerging from the UC Davis protests and in another post highlights the callousness of the pepper spraying:

Watch that first minute and think how we’d react if we saw it coming from some riot-control unit in China, or in Syria. The calm of the officer who walks up and in a leisurely way pepper-sprays unarmed and passive people right in the face? We’d think: this is what happens when authority is unaccountable and has lost any sense of human connection to a subject population. That’s what I think here.

Also at The Atlantic, Garance Franke-Ruta offers a round-up of videos of violent police crackdowns against the Occupy protests. Ta-Nehisi Coates asks us to place the pepper spraying in a broader cultural context:

Not to diminish what happened at UC Davis, but it’s worth considering what happens in poor neighborhoods and prisons, far from the cameras. I’m not saying that to diminish this video in anyway. But I’d like people to see this a part of a broad systemic attitude we’ve adopted as a country toward law enforcement. There’s a direct line from this officer invoking his privilege to brutalize these students, and an officer invoking his privilege to detain Henry Louis Gates for sassing him.

Leadership

Cathy Davidson calls the pepper spraying a “Gettysburg Address moment,” in that “moral authority and moral force needs to be eloquently articulated before this historical moment devolves into violence and polarization.” She asks college presidents nationwide to demonstrate wisdom, passion, and moral vision.

University of California system President Mark Yudof issued a response to the pepper spraying. In response to his letter, Lili Loufbourow offers what is, in my opinion, the best-titled post on the whole clusterfuck: “Dear Mark Yudof: The Cemetery You Manage Can Hear You.” (The reference is to Yudof’s quip to the New York Times that “being president of the University of California is like being manager of a cemetery: there are many people under you, but no one is listening.”) Loufbourow gives us a blow-by-blow analysis of UC administration response to incidents at Berkeley and Davis–it’s worth a read, but if you work for the UC or a similar system, be sure you take your blood pressure meds first. See also the e-mail messages from UC Berkeley Chancellor Robert Birgeneau et. al. to see in even more detail how the rhetorical sausage gets made.

Sherry Lansing, the chair of the UC Regents, released a carefully scripted and unpersuasive video statement. In a complete monotone, she declares, “We Regents share your passion and your conviction for the University of California.” To demonstrate the Regents’ dedication to the UC community, they’re opening up their next teleconference meeting to public comment for a whole hour. How generous!

Katehi

It ends up UC Davis Chancellor Katehi is one of the authors of a recent report recommending the end of university asylum in Greece. Niiiiice.

Here’s Katehi leaving a press conference and being greeted by a phalanx of students, faculty, and staff that was, by some estimates, 1,000 people strong:

She is accompanied by the campus chaplain, Rev. Kristin Stoneking, who wrote a moving post on why she walked Chancellor Katehi from the press conference.

I’m so proud of UC Davis students right now. For once I say this without sarcasm: Stay classy.