Look out–this one’s going to be especially rambly.

Back at this blog’s former home, I blogged more frequently about depression than I have lately–so much so that for a while, The Clutter Museum was ranked #1 in Google for the phrase “depression in academia.”

Fortunately, I’m not dealing with those demons at the moment, but in the past couple of years, it’s become clear that another (usually very mild) disability is ascendant in me: asthma, bronchitis, and pneumonia.

I’m one of those people who tends to ignore my disabilities until they become visible to others. Learning self-care (prevention and remediation) has been a long, hard road.

I began ignoring illness when I was young. I don’t think I’ve ever blogged about the thyroidy years, but when I was 11 years old and just starting horseback riding lessons, I began to feel really shaky and dizzy and just generally weak about midway through my lessons. One riding instructor thought it was low blood sugar. My pediatrician thought I might be allergic to horses (perish the thought!). Eventually, though, the pale, liver-spotted Dr. C turned his turkey-waddled head toward my father and noticed a pale scar extending across my dad’s throat. “Is there,” he asked, “a history of thyroid disease in your family?”

Why, yes, it ends up there is.

Thus began a long, long journey through several primary-care physicians and assorted specialists until I found a wild-haired little endocrinologist who wore a tweedy three-piece suit to his office in what was, to put it mildly, not the best part of Long Beach. Dr. B wrestled with my thyroid for years, trying everything—at one point having me take eight pills a day, spaced as evenly across the day as possible (a perfect prescription for a busy high school student, yes?)—before becoming exasperated by a series of inexplicable blood tests (“Were you hit by a truck?”). He explained there were two doors ahead of me: Door number 1, he said, was surgery. Door number 2, radiation. He detailed the risks of each procedure.

I looked at the giant scar on my dad’s neck and opted for radiation. We had recently had the talk I imagine all parents eventually have with chronically ill teenagers who still believe in their own invincibility, symptoms be damned. Dad pointed out, rather bluntly, “You could die.”

Oh.

Furthermore, my parents made clear I couldn’t go to college until I was healthy. I was seventeen. Tick tock.

So soon I found myself greeted in a local hospital by a balding man in suspenders, bow tie, and lab coat, who announced, “Hi! I’m Dr. M. I’ll be your nuclear radiologist for the day.” I sat in a chair; an intern shielded me with a lead apron and wheeled a tray before me. He picked up a lead vessel, unscrewed the lid, and placed a plastic bendy straw in it. Everyone retreated to the doorway. “I’m told,” Dr. M said, “it tastes like bad tap water.”

I drank. It did.

Dr. M told me not to “sweat, spit, or pee on anyone for three days.” I was to use only plasticware at meals, stay 6 feet away from anyone under age 45 (3 feet from anyone over age 45), and flush twice.

Because the radioactive iodine I had just swallowed would, he explained, basically shoot all my thyroid hormones into my system at once, I could expect an elevated heart rate for a while. He prescribed Inderal in anticipation. Inderal gave me night terrors and hallucinations, neither of which I had experienced before. (The night terrors continue to this day.)

Shortly after I drank the radioactive cocktail, my hair started falling out. My vision was already crappy, but I didn’t think it was bad enough that I needed to wear glasses all the time, so my first indication of the hair loss was a change in the carpet color in front of the mirror where I brushed my hair. Fortunately, my I didn’t lose all my hair, though I could perform the fun parlor trick of grabbing a fingerful and yanking it out painlessly. (Surprise: I didn’t date in high school.)

After blood tests every week for a year, we found the correct dose of synthetic hormone, and now I test annually. Yes, my weight fluctuates—after all, I have no thyroid function to speak of—but eventually we found a maintenance dose that at least makes me feel human.

A hypothyroid, however, also can bring with it extra depression. Wheeee! Thanks to the wonders of the internet, I began to read about depression and realized, hey, maybe I should get that checked out, too. By that point (age 25) I was dating Fang, and he made sure I saw a therapist. She, in turn, made sure I saw a doctor who could prescribe some antidepressants.

Problem (sort of) solved. My depression waxes and wanes, as dysthymia is wont to do. I’m an exceptionally high-functioning depressive, and I’ve never missed a day of work because of it. Only once did I get so miserably behind on my responsibilities that I had to confess to a colleague I was struggling with depression. Fortunately, our work together addressed UC Davis’s accommodation of students, faculty, and staff with disabilities, and she both studied disability and lived with one; her level of understanding and compassion was high, for which I am grateful.

So, the tally:

- Hyperthyroidism: eradicated.

- Depression: manageable.

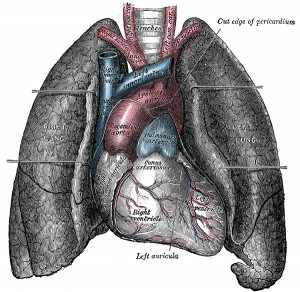

That leaves the lungs. Many of us who grew up in the Los Angeles basin in the 1970s and 1980s breathed in a wretched stew of exhaust and other chemicals, and—who knew?!—it ends up there are long-lasting effects. I had chalked up my earlier failures to run ever faster (I topped out at a 6:58 mile in eighth grade) to my thryoid issues, but in eleventh grade, when I began playing French horn in three music ensembles at school, the chest pains began. At first, because I hadn’t yet solved the hyperthyroidism (that would come the following summer), I thought the pain was related to the general fatigue the thyroid curse engendered. The usual cardio tests ensued until during one exam, my physician lightly tapped my chest and I recoiled in pain. “Ah,” he said, “asthma!”

Going to college in Iowa didn’t help; forty percent of Iowans smoked, there weren’t a whole lot of smoke-free indoor spaces, and windows remained closed much of the year due to the cold or heat. My lungs were not pleased. That said, one summer there I took up running and regularly ran for 45 minutes to an hour, the longest I’d ever been able to run until that point. I went home to Long Beach and followed my sister on an eight-mile run, but lost interest in running when winter set in (cold air is another asthma trigger). Since leaving Iowa, there have been times I’ve tried to take up running, and I’ve followed many different plans along the lines of Couch to 5K, but I find I have to stop running just shy of one mile.

One mile!

I’ve talked to my physician about this, and her advice is to use the inhaler before I exercise. So I do. It makes very little difference.

Fortunately, I’m not looking to become a long-distance runner, but I admit I look at my friends’ marathon and half-marathon and 5K and 10K photos on Facebook, as well as their Runkeeper updates there, and I get a bit wistful.

And it’s difficult to establish a regular exercise routine when every head cold inevitably goes to my lungs and becomes bronchitis or—in a disappointing turn since I moved to Boise—pneumonia. I can establish a good groove at the gym, and then bam! no workouts for months because: recuperation. (I very rarely miss work due to these illnesses because I have an overdeveloped sense of commitment to my students and colleagues, but working out is out of the question.)

Now I’m sick again, and it’s going into my chest. Today was a beautiful spring day, and I would have loved to spend it gardening, bicycling with Lucas, or hiking in the foothills before the rattlesnakes emerge.

Fang is, of course, frustrated beyond words. Dealing with a regularly ill spouse is no fun, and he does a great job of gracefully taking over my share of housework and childcare.

But I’m realizing I’m falling into an old pattern of living with something (thyroid, depression, asthma) without sufficiently addressing it until I’ve suffered quite a bit. I see reduced circumstances as normal, as inevitable. In this case, however, I’ve talked to my doctors, and all the tests say my immune system is fine. The doctors just say to rest. And so I sit still. And I get flabby. (Even lifting weights is tiring.) And it’s maddening.

In the past year, I’ve begun to really feel the effects of aging: the stiffness, the pull of gravity, the graying hair. (I’m 37.) I want to move, to get fit—I want to keep up with Lucas—but every effort meets with failure. I need to find a new way of thinking about my physical abilities going forward, one that encompasses a different kind of health and fitness than I see in my Facebook feed and in every damn mainstream media outlet.

Comment zen: I’m not looking for medical or fitness advice right now; please don’t give me any. If you know of resources that address how to deal psychologically with changing physical circumstances, however, I’m all ears.