This post is another response to an assignment in Critical Instructional Design. This week’s prompt:

This week your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to dismantle and re-mantle one common assumption about instructional design. We encourage you to tackle one of those assumptions that you hold most closely—because discomfort can often be terrifically productive.

I’m tackling Bloom’s taxonomy.

Why? I find I refer to it often, but I realize I’m frequently using it as shorthand for something else.

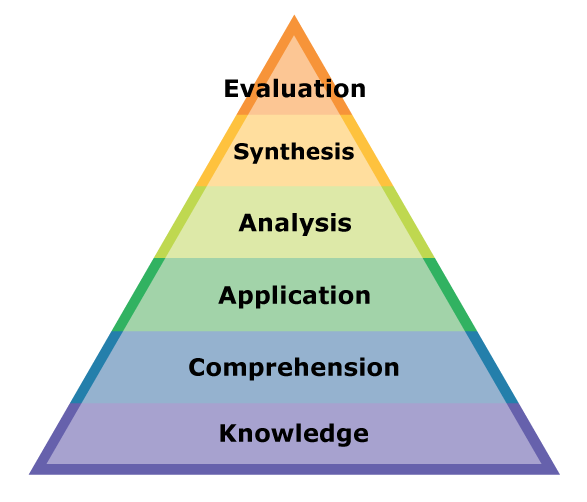

Bloom’s taxonomy emerged from a series of educational conferences in the late 1940s and early 1950s, but ended up being named after Benjamin Bloom, who served as chair of the committee of educators that formulated the taxonomy. Those of you who are teachers or professors very likely will have seen this diagram or one like it:

Source: Learn NC, “Bloom’s Taxonomy,” used under a Creative Commons license.

This is actually one of three taxonomies and represents what the committee termed “the cognitive domain.” It’s the part of the taxonomy that remains most popular in higher education. The way I’ve seen Bloom’s taxonomy described—and honestly, how I usually explain it—is that these cognitive skills build on one another as they grow increasingly complex. The common implication, then, is that these skills need to be scaffolded—though I confess in my classes I’m not particularly good about careful scaffolding. In my courses I try to get students into application, analysis, and synthesis almost immediately.

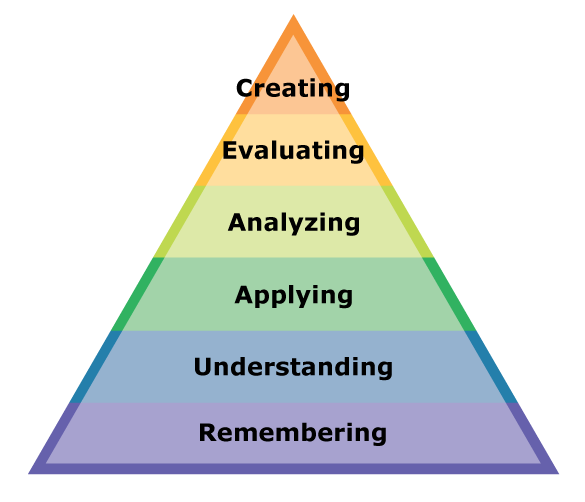

In the 1990s, some of Bloom’s students revised the taxonomy so that it looks more like this:

Source: Learn NC, “Bloom’s Taxonomy,” used under a Creative Commons license.

Lorin Anderson, one of the authors of the revised taxonomy, described the process and previewed the changes in a 1999 paper; Anderson explained that the next taxonomy emphasized the contexts in which cognitive processes take place and acknowledged more than the academic context—the authors added two additional knowledge categories or dimensions: the “strategic/motivational” and “social/cultural.” Anderson writes,

The first, strategic/motivational, recognizes the importance of knowing as a legitimate educational goal. This category contains what has been termed metacognition and includes the learning strategies students employ, the links they make between their efforts and their accomplishments, and their perceptions of themselves as people and as learners. The addition of the second category, social/cultural, reflects our appreciation of the cultural-specificity of knowledge. It also recognizes the role of social learning theory in explaining how students learn.

The revision, therefore, infused the original taxonomy with additional complexity and nuance. Whereas the original taxonomy suggested students should be climbing ever upward on the chart, another of the creators of the revised taxonomy, David Krathwohl, made clear that students may more freely move up and down the chart:

Like the original taxonomy, the revision is a hierarchy in the sense that the six major categories of the Cognitive Process dimension are believed to differ in their complexity, with remember being less complex than understand, which is less complex than apply, and so on. However, because the revision gives much greater weight to teacher usage, the requirement of a strict hierarchy has been relaxed to allow the categories to overlap one another.

Krathwohl implies, then, that the skills don’t necessarily need to be scaffolded. This freedom from moving systematically up the taxonomy frees up faculty to take risks as they pose greater challenges to their students, asking them to take cognitive leaps rather than plodding steps.

Krathwohl added an additional layer to the revised taxonomy by suggesting the cognitive skills be used as column heads across the top of a table, with different varieties of knowledge—factual, conceptual, procedural, and metacognitive—forming the row headers. Instructors could place their individual learning objectives in the table’s cells, mapping in one visual what kinds of cognitive skills and knowledge a course aimed to develop in students. While filling out this taxonomic table may feel a bit mechanical to some instructors (myself included), the completed table makes transparent what kinds of knowledge and skills will be cultivated in a course. Should all of these skills and knowledge be grouped into a single area of the table—say, the upper-left quadrant, which focuses on remembering, understanding, and applying factual and conceptual knowledge—the instructor may want to reconsider the course objectives. Some instructors may be comfortable conducting a 100-level course in this quadrant of the table, but uncomfortable if their upper-division courses also fell there.

Criticisms

Bloom’s taxonomy in both its forms has been both popular and influential, but it has not been free of criticism. As Robert Marzano and John Kendall note in The New Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Bloom’s original taxonomy has proven especially useful in evaluation, though less influential in curriculum design. In particular, Marzano and Kendall write, developers of the standardized state tests that arose in the 1970s leaned on Bloom’s, sometimes heavily, to define skill levels. In the past few decades, such tests have come increasingly under attack from parents and teachers alike. Anderson acknowledges Bloom’s utility in and application to such evaluation, but defends the new taxonomy from critics who might say the original taxonomy lends itself to oversimplified assessments: “We believe that the diversity of cognitive processes represented in the taxonomy requires a comparable diversity of assessment strategies and techniques.”

That’s an important acknowledgement and correction, as one of the biggest criticisms of the original Bloom’s taxonomy is that it’s unscientific and out of step with current theories of learning. In particular, the levels, which Bloom et. al. claimed were hierarchical, are actually quite muzzy. Drawing on others’ criticisms of Bloom’s, Marzano and Kendall point out that higher-order skills can be prerequisite to allegedly lower-level ones. For example, they write, analysis of a subject can be central to comprehending it.

Syntheses of Bloom’s

Those who criticize the original taxonomy’s embrace of hierarchical levels of cognitive skills can indeed hold the original taxonomy responsible, but the synthesis of Bloom’s with other learning theories strengthened this hierarchy. Take, for example, the three theorists perhaps best known for their uses of various kinds of scaffolding: Vygotsky, Bruner, and Rogoff. Each scaffolding theory holds that learners need assistance, usually from other people, in moving to higher orders of thinking and understanding.

These theories emphasized the social aspects of learning: people learn in community, whether it be in a formal classroom or in an informal setting. And once we introduce the social component, the multitudinous learning scenarios become impossible to track. As our networked, digital age has increasingly made clear, knowledge lives and thrives in networks, and it’s situated in bodies (h/t Donna Haraway). Depending on which nodes (people, learning artifacts, contexts) are connected and activated at any given time, different kinds of learning take place and different knowledges are created. As John Spencer suggests in a blog post, the original taxonomy’s clean modernism does not stand up in a postmodern age. That said, the modernist tendencies of Bloom’s are written right into the model’s name: it is a taxonomy; it names, classifies, and orders.

Even in the midst of this analytical chaos, however, Bloom’s remains useful as a shorthand in introducing learning theory to faculty who have never considered the subject. I frequently refer to “pushing students up the pyramid.” On the one hand, the metaphor is a bit coercive. On the other hand, it suggests we have students’ backs and are trying to support them in their journey. I’ve used the expression with students as well as faculty, and it seems to help students understand what’s going on in my (to them) unconventional online course. I even used Bloom’s to explain my course’s activities in a recent wrap-up post in the online course I taught in the spring.

Bloom’s, scaffolding, and employability

I want to take a look at that same closing post from my online course, as it captures a moment when I was trying to make sense of the first course I’d taught fully online, and it references Bloom’s, then immediately swoops into a discussion of career outcomes.

That course, HIST 100: Themes in World History — Engineering the Past, is meant to serve primarily as a general education course for non-majors and secondarily as a place where we might recruit majors. It was my first time teaching online and my first time teaching world history (which I last took in eighth grade), and I complicated the semester by using WordPress as an institutionally unsupported LMS and by trying to use as much free course material as possible. It was messy and not too far beyond what Silicon Valley types might call a Minimum Viable Product. When I teach it again, it will look very, very different.

I’m fortunate to be at an institution where we aren’t mandated to use the supported LMS, Blackboard, though I did use Blackboard’s gradebook because students like to have a place to track their grades, and I didn’t trust any gradebook I could set up in WordPress would be compliant with FERPA.

There are many benefits to working outside the institution’s LMS—benefits I’ll try to remember to elaborate in another post—but one disadvantage in teaching a 100-level online course on a platform that’s new to students is that it requires a good deal of technological scaffolding and hand-holding. I’ve used WordPress in my face-to-face courses, where students can easily help one another with technical questions before, during, or after each class meeting. In an entirely online general education course, however, there doesn’t tend to be the same sense of community because, at least at my institution, many of the students sign up for online courses hoping they’re a smaller time commitment than face-to-face courses. Students enter the semester, then, already reticent to invest time, let alone emotional energy, into such a course.

Accordingly, I found I needed to show students how to do simple technological tasks, such as logging into WordPress, writing and publishing a post, adding visual or audio media to a post, collaborating via Google docs, or finding a journal article in the library’s databases. As the semester progressed, I expected students to remember what I had already showed them how to do, then apply those patterns to other technological challenges in the course—e.g., finding other library resources or collaborating digitally on a much less structured group project.

It was clear to me some students felt more than a little lost during the course, and for every student who gave polite voice to their frustrations or confusion, I suspect two or three remained silent. At the end of the course, then, I felt the need to tie everything up with a neat bow, explaining that what may have seemed like a scattershot approach to world history was actually (somewhat) carefully planned to provide students with a lower-division course experience that expected more of them than a typical 100-level course.

Furthermore, although I had not done so intentionally, I realized many of the course activities and outcomes aligned with an entirely different but relevant taxonomy: my university’s “Make College Count” initiative, which encourages students to find opportunities to practice the skills employers most seek:

- analyzing, evaluating, and interpreting information;

- thinking critically;

- solving problems;

- taking initiative;

- contributing to a team;

- managing time and priorities;

- performing with integrity;

- effectively communicating orally;

- building and sustaining working professional relationships.

I don’t like to think of higher education as vocational training, but when I view many of my courses from my students’ perspective, I understand students see college as key to developing the knowledge and skills that will let them earn a better living in a state that ranks first in the nation for minimum-wage jobs per capita. Student can develop these skills in any number of disciplines, but as an advocate for the humanities, I try to ensure students practice such skills while coming to appreciate the value and utility of the humanities in everyday life.

And so, yes, I practice scaffolding in some of my courses, and I found it to be especially valuable in my online course. I scaffold skills—from collaborating with others in a digital environment to analyzing material culture to better understand the habits, beliefs, and values of artifacts’ users—more than I do content. Content is just a way for students to get to the skills. And so I tend to skip very quickly over remembering and understanding in favor of emphasizing application and analysis through the act of creating a digital project that synthesizes text and multimedia elements.

Looking forward

So. . . What will I change in my courses and my instructional design practice now that I’ve taken a closer look at Bloom’s taxonomy and its critics?

Honestly, not much. Bloom’s remains a useful tool for me in my current context. Were I teaching at a selective small liberal arts college or an R1 university, both of which often have more middle-class and wealthy students than my institution does, I might not have to think as explicitly about how the skills we use in class affect students’ immediate career prospects. Like the educators who reformulated Bloom’s Taxonomy in the 1990s, I’m compelled to take the learning context into account.

Still, I appreciate the opportunity to reconsider, and then defend, one of my core ways of thinking about skills and outcomes in my courses.