Sisyphus at Academic Cog has thrown down the gauntlet, asking others to share that most dreaded of exercises–the statement of teaching philosophy.

When I worked in a teaching center, I had to read a lot of these by grad students and postdocs going on the job market, and by faculty who wanted to include one in their tenure and promotion packet. And hoo boy, did I read some bad ones. Because they’re so easy to write poorly. Plus, they tend to all sound alike because their writers imagine there’s something that reviewers expect to see in these statements. And maybe most reviewers do look for something specific. . . but at the point I last revised my statement I was more interested in remaining authentic to my experience in the classroom and less enamored with conscientiously using the “correct” rhetoric of teaching and learning.

So when I revised my statement for my last round on the job market, I decided I wanted to structure it differently. I’m still not completely satisfied with it, but here’s where it stands now:

When I was a graduate student instructor, I found writing a statement of teaching philosophy to be a relatively easy task. I had only my experience to speak from, and I was fortunate to be teaching subjects students seemed naturally to enjoy—or that they could be persuaded to enjoy. I had complete freedom in selecting a curriculum, developing activities and assignments, and assessing student work, and my teaching evaluations were very strong.

After spending three years advising faculty, grad students, and postdocs about teaching, my perspective on teaching is considerably more nuanced. Thanks to the hundreds of faculty who have come to me for help, who have confided in me, and who have trusted me to interview their students, I have a much broader, and more seasoned, perspective on teaching, and the place of teaching, at the large research university.

In a typical teaching philosophy statement, I would (1) state my learning objectives for my students, (2) illustrate how I used assignments and activities to fulfill those learning objectives, (3), state how I evaluated student learning outcomes, and (4) make some grandiose statements about interactive, student-centered learning. However, in the past three years I’ve read more than a hundred of these, and I fear a certain tedium sets in after reading more than a few. Accordingly, I will address these teaching concepts, but less directly, through vignettes that I hope illustrate my commitment to teaching all students, my deep thinking about the relationship between theory and praxis, and my very practical approaches to common classroom challenges.

Dealing with that guy

When I encourage faculty to incorporate more interactive learning opportunities into their courses, they frequently express the fear that students won’t talk, and that they’ll find themselves stuck in an awkward silence in front of a hundred or more students. In my classroom, however, the challenge frequently is less getting students to speak than to encourage one student to talk less. Almost every undergraduate course I’ve taught has had “that guy,” a student—and 90 percent of the time it’s a young white man—who sits in the first or second row of the classroom, two or three seats to my left, and who must comment on everything, to the point that the students sitting behind him are rolling their eyes.

My approach to such a student is to take him aside after class and recruit him to my cause of reaching all learners, of ensuring all voices get heard. I thank him for the comments that have been spot on—and I cite those specifically—and then tell him that some students need more time to formulate their thoughts before speaking. Would he mind waiting a bit before speaking so that these students can get a chance to participate? I tell him to feel free to e-mail me with any thoughts he didn’t get a chance to share. So far, this tactic has worked every time, and it’s clear from their contributions to class that these students become better listeners and more critical thinkers as a result of that listening.

Learning with students with disabilities

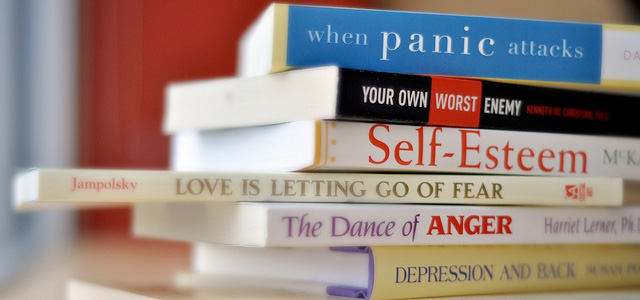

Both because I’ve found most students respond well to images and video and because I’m a visual learner myself, my classes tend to be highly visual in nature. I may share a dozen or more images during a single class meeting. When I first had a blind student in my classroom, however, I realized this practice needed to be supplemented with better audio description and alternative ways of accessing the material. I was fortunate that the student was willing to work with me and was forgiving of my failure to plan for visually impaired students when I developed the course.

The experience of working with this student, and since then with other students with physical and learning disabilities, made me become interested in the universal design for learning, a set of principles that calls for giving learners multiple ways of acquiring information and knowledge, of engaging with material presented during class time, and of demonstrating what they have learned. I’m now chairing the teaching and learning subcommittee of the campus’s electronic accessibility steering committee, where I have the opportunity to ask hard questions about—and provide tentative answers to—campus policies. For example, UC Davis’s new general education requirements call for students to demonstrate visual and oral literacy. How does a blind student develop visual literacy, and how might we measure it? How does a student who does not speak demonstrate mastery of oral expression? I’m thrilled to have the opportunity to collaborate with faculty and students in addressing these issues.

Helping the general education student research and write papers

The departments in which I have taught typically offer a large number of courses that help students fulfill the GE writing requirement. Accordingly, my classes tend to have a large number of non-majors who have not had sufficient opportunities to write argumentative papers or undertake research. One fifth-year managerial economics student confessed to me that she had not written a thesis statement since fall quarter of her first year, and I suspect she was not alone in this experience. Such students pose a special challenge, and I meet it by spending extra time helping students search the library’s databases, by offering multiple extra office hours (as many as 30 hours one week when I was a graduate student), and by partnering with reference and instructional librarians.

It also means I spend a portion of each course reviewing the principles of writing with my students. Some faculty have told me they don’t have time for such instruction as they have too much material to “cover.” My experience has been the opposite; by encouraging students to undertake research on topics related to the class (but not explicitly covered during it), and then asking students to share their research with the class, students are exposed to far more material, and have a more meaningful engagement with it, than they would if I had simply lectured or had them read about it. My classes are about discovering and uncovering, not “covering.”

My goal in every course is to make myself approachable to students and yet ultimately dispensable. I teach my students to ask thoughtful questions, conduct research, and express themselves through multiple media. I design my classes to help students learn to better engage with the world, with the hope that they will take steps toward effecting positive change in it.

After my experiences at the public history conference today, I’m thinking it’s time for me to write a teaching philosophy statement that’s specific to teaching public history.

What are your thoughts on teaching philosophy statements? Pointless exercises, valuable opportunities for reflection, or something in between?