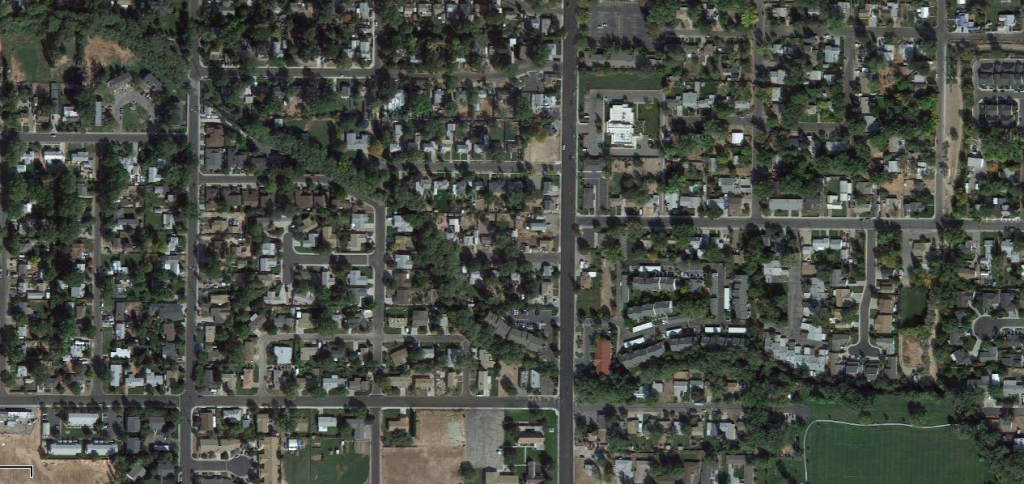

I had never lived in a city striated by irrigation ditches, so when I arrived in Boise, I was surprised to hear water coursing under a sidewalk, come across a completely silent and barely rippled canal running behind houses, glimpse a tiny waterfall disappearing under a street, or discover what appeared to be a happy, fast little stream rushing along the perimeter of a park. (In the image above, the canal is marked by trees, and runs from lower right to upper left.) In the summer, many homeowners receive irrigation water one day a week, but it floods their yards, sometimes inches deep. For someone from drought-stricken California, this seemed beyond luxurious–an egregious waste–but still I cooled my feet in it last summer when the swimming instructor’s backyard was five inches deep beneath the shade trees.

In my neighborhood, there’s a stretch of irrigation canal lined by a dirt road that, although it’s marked “no trespassing,” attracts solitary walkers and runners, families with small kids headed toward a local playground, and lots of people with dogs, some of whom splash in and out of the canal. During much of the year, it has no water in it, but when it does, I like walking along it. The most life I’ve ever seen in the water is half a dozen mallards and tufts of green algae, but its far bank is marked by dilapidated remnants of earlier generations, and it’s overgrown with all kinds of flora. If I hit it at the right summer moment, I can grab a few apricots from a feral tree near the park.

It’s sort of idyllic, this intrusion of water into the spring and summer suburban landscape. But television ads warn us not to let our children near the canals because canals mean death. And indeed, even the stillest of them may: who knows what chemicals they pick up as they cross the patchwork of urban, suburban, and rural lands? Even a quick glance at irrigated lawns in the spring reveals noxious agricultural weeds whose seeds the water deposits in the suburbs. Noxious weeds bring herbicides, which seep down into the soil and back into what Mark Fiege has termed the ecological commons.

Still, I’m drawn to the canals because they suggest the potential for erosion. Unlike the rivers of my native Southern California, they’re for the most part not cemented into their banks, and while the possibility of their wandering is faint, it exists—some upstream slip-up, some unclosed gate or broken meter, and the water overflows its banks and cuts new channels.

There’s always been a similar tension for me—intellectually, psychologically, and emotionally—between structure and disruption. As a K-16 student, for the most part, I benefited from my ability to flow through established channels. By the time I started my third (and thankfully final) graduate program, however, I began to realize that established channels were no longer particularly attractive to me; I had pretty much mastered the art of the seminar paper and had come to resent much of what I was being asked to read. (I took the authors seriously, and read every word, and I appreciated their politics, but the language and attitude of these texts were just so off-putting that I felt compelled to take a vow of comprehensibility–never to write like a typical lit crit theorist or cultural studies scholar. Fortunately, I had mentors whose training was outside those fields.)

I began to look outside school for opportunities. During grad school, I started a freelance writing and editing business as a side hustle, I held a series of positions at a local science center, I consulted on an outdoor science ed program, and I developed and managed a large, popular science exhibit at the state fair. When I graduated in 2006 without an academic job, I took on a couple of fairly well-paying “alt-ac” jobs at the university and seized the opportunity to adjunct in a graduate museum studies program. I enjoyed much of this work, and I adored some of it, and I always appreciated the additional income. Shortly before interviewing for my current job, I founded a consulting firm with a colleague, but sold my ownership in it when I moved to Boise.

In the intervening time, I’ve learned to play the academic game fairly well, though there are certainly aspects of it that I could embrace more fully. In an alternate universe, there’s a Leslie who puts all her intellectual efforts into peer-reviewed writing; she has many journal articles and a book under contract with a university press. She reads papers at disciplinary conferences. She writes book reviews. In her spare time, she has kept up with her French horn studies and plays in a community wind band. Her home office is organized.

Actual me, meanwhile, is overflowing the intellectual and emotional banks of a canal that cuts across the landscape of too many disciplines. I’m more likely to pick up Fast Company or a book on digital journalism than I am The Public Historian or the latest monograph from Duke University Press. My stack of books to read comprises a mix of museum studies, poetry, programming, fiction, and business. I’m more likely to have a Python tutorial or WordPress stylesheet open on my computer than I am to be mining JSTOR. Most days, I’d rather be writing essays for a popular audience than papers for academic journals. It’s not that I don’t enjoy or have given up those other things—it’s just that they are no longer enough.

This overflowing—this mania of research and writing about technology, culture, and entrepreneurialism—has resulted in flora sprouting wildly on the banks of the relatively narrow canal of what’s expected of an assistant professor of history at a university known more for its football team than its graduation rate. And some of those flowers have drawn passers-by into conversation in a way that my traditional academic research never has.

I’ve written before about this restlessness that manifests sometimes as a strangely driven lack of focus. And it’s a weird restlessness, because I love my current job—the students, my colleagues, the autonomy I’ve been granted because I’ve already pretty much checked the boxes for tenure—and I’m succeeding here.

Honestly, as an adult, I’ve always lingered in the weeds of what’s expected. But now economic considerations—personal and structural (the situation in Idaho schools, for example) are driving me to think about how to take my unique combination of skills, passions, and expertise to a different context, one in which, ideally, I’d be fairly and perhaps even generously compensated for my work.

That’s a very difficult thing for me to admit. As an English major and writer, as the daughter of public school teachers, and as a student inculcated by the economic and structural criticisms inherent in cultural studies, I picked up the message that pursuing economic gain beyond the very modest is something that only shallow, selfish people do. And honestly, if it was just me, I could live comfortably in a small apartment or carriage house here in Boise. But I have a family, and between the costs of various lessons for the kid, the expected contributions to his criminally underfunded school, the cost of maintaining two aging cars (because we live in a city without good public transportation), and various ever-rising family medical costs, the salary I’m paid at Boise State isn’t sustaining us in a way that’s comfortable.

The problem, of course, is I don’t know what my next stage is going to look like, or when it might start. I’m going to have to open up the gates on my intellectual and emotional canals, and let the water flow. Who knows what seeds it carries, and what might grow?

Epilogue

I wrote all of the above more than a week ago, and in the last week, I’ve felt the shift accelerate. I finished up the semester. I helped the boy with one of our semiannual purges of his room in search of toys, games, and clothes to donate, and I realized how quickly he’s growing up and all the things I want for him that I haven’t found here. I took an overnight retreat with a friend that helped me see the bigger geographical picture and gave me time to read and scribble some notes about me instead of about my research and teaching. I’m starting to pack for my next research/conference trip, this time to Davis (for archives) and to San Francisco (for Adacamp, an unconference for women in open-source technology), and both aspects of the trip are providing all kinds of food for thought—plus there’s the nostalgia factor of visiting my old stomping grounds. And then I felt drawn to apply for a spot at another interesting event later this summer, and I secured a place there, too. This last opportunity, which I hope I can say a tiny bit more about soon, is going to bring me into contact with all kinds of amazing people with whom I might not otherwise cross paths, and I’m thrilled about it.

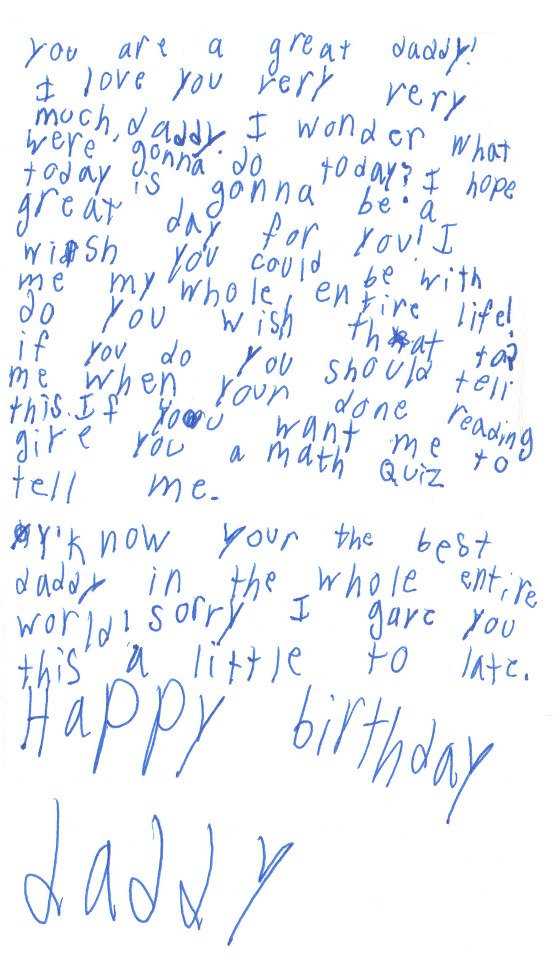

Plus, my birthday is on Sunday–I’ll be 38–and the date always prompts some soul-searching.

Maybe nothing life-changing will come of this reflection and experimentation–I am, after all, a person of many ideas and insufficient time to develop them all, so I have to leave some at the side of the canal, out of reach of its waters–but I’m feeling that strange blend of confidence and impostor syndrome that usually means I’m poised for some serious professional, personal, and intellectual growth.