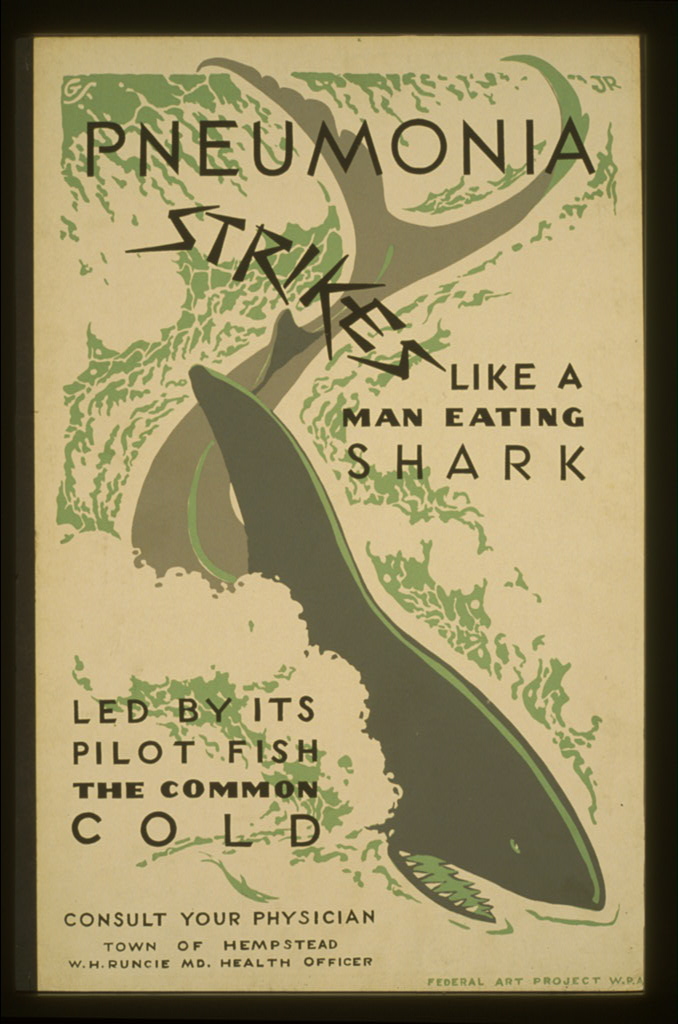

As if antibiotic-resistant pneumonia for me and a nasty chest cold for Fang weren’t enough, the household gods decided to toss in another challenge. Here’s Lucas’s op-ed from New Year’s Day:

An appreciation

I have to admit, when Fang said we should sign the boy up for Taekwondo, I was a skeptic. My pacifism runs deep, and I was worried Taekwondo involved a lot of fighting. We had already talked at length about how Lucas was going to be a big kid, and if he happened to inherit Fang’s occasionally short temper, he needed to know how to control himself; was teaching him to fight really going to encourage reflection and nonviolence?

I have to admit, when Fang said we should sign the boy up for Taekwondo, I was a skeptic. My pacifism runs deep, and I was worried Taekwondo involved a lot of fighting. We had already talked at length about how Lucas was going to be a big kid, and if he happened to inherit Fang’s occasionally short temper, he needed to know how to control himself; was teaching him to fight really going to encourage reflection and nonviolence?

Today, in Taekwondo Lucas has reached the level (and you can imagine how I feel about this belt color) of “Camouflage – decided,” meaning next time he tests he’s eligible to earn his green belt. When he began Taekwondo more than a year ago, he was physically awkward and timid; in fact, just a couple months ago we gave up gymnastics lessons after about a year because he wasn’t progressing at all. He couldn’t hop on one foot without falling over. He couldn’t even jump and land simultaneously on both feet.

Worse, in school and on playdates, he was being bullied—by much smaller kids–and had no idea how to deal with it. In both kindergarten and as recently as this fall in first grade, his annual character goal was learning how to tell people how he feels when they treat him poorly.

We’re fairly laid back as parents go, but those details raised some red flags for us, so when the owner of the martial arts school invited Lucas to join the leadership club, where kids get practice interacting with and teaching other kids, we jumped at the opportunity, even though the cost is a bit of a financial stretch for us. (Ditto for a run of weekly 30-minute private lessons with an instructor who really seems to “get” Lucas, but the ROI on those has been great, too.) The leadership club membership means Lucas can attend as many classes each week for which he’s qualified, and he has embraced the classes wholeheartedly, typically attending three classes a week.

We’re fairly laid back as parents go, but those details raised some red flags for us, so when the owner of the martial arts school invited Lucas to join the leadership club, where kids get practice interacting with and teaching other kids, we jumped at the opportunity, even though the cost is a bit of a financial stretch for us. (Ditto for a run of weekly 30-minute private lessons with an instructor who really seems to “get” Lucas, but the ROI on those has been great, too.) The leadership club membership means Lucas can attend as many classes each week for which he’s qualified, and he has embraced the classes wholeheartedly, typically attending three classes a week.

I haven’t written much here about Lucas, as he’s really becoming his own person, and, as many a blogging parent has noted, after about age four or five, it doesn’t seem as appropriate to blog all the milestones. But the change we’ve seen in him as a result of a combination of parenting, his very special school, and especially Taekwondo has been tremendous.

As I mentioned, within the past six months or so, we were still working with Lucas on landing on two feet after jumping, and he wasn’t getting much air. Here he is at tonight’s Taekwondo class. (Apologies for the blurry photos–I got tired of lugging around the SLR, and I’m still learning to use this point-and-shoot camera.)

He’s showing confidence, strength, and even a bit of agility. We have conversations about the character themes of each 9- or 10-week session—the most recent was perseverance—and you better believe we’re milking the school’s question “Is that a black-belt attitude?” at home for all it’s worth.

A lot of the boys and girls enrolled in the classes appear to be mainstream, rough-and-tumble, tough little kids, and clearly they’re benefitting from the instruction. But I just want to highlight how much the classes, and the whole atmosphere of the school, have helped our sensitive and awkward boy develop into a much more confident seven-year-old boy. If you find yourself in a similar situation with your child, I recommend you find a good Taekwondo school (this is the second one we tried, and it really clicked, while the first one did not) and give it a chance.

We owe a big, and ever-growing, debt of gratitude to Heather Grout Neitzell, who teaches courses and owns the studio with her husband, as well as to the various instructors and junior instructors, but most notably Lucas’s regular instructors and assistant instructors, Ms. Strader, Mr. Garrard, Mr. Putzier, and Mr. Fenello. Big thanks to all of them for helping our boy make up some lost ground in confidence and athleticism. We still have a long way to go, but because we’re seeing such great results, we’re committed to continuing with Taekwondo for as long as Lucas wants to participate.

Into the heart of whiteness and gun violence

A couple weeks back, before waves 1 and 2 of the pneumonia hit, I promised to write a series of posts about gun control. Meanwhile, there has been a ton of insightful writing about gun violence in the United States, so my series here may feel more like a round-up than a new contribution. That said, I feel moved to collect those links into themed posts for those who might have missed some or all of them.

Here is the first of those posts.

Photo by Jonathan Leopard, and used under a Creative Commons license

After Barack Obama was elected to the White House but before he took office, Fang and I went to Tucson to celebrate Thanksgiving with his family. While there, we reconnoitered with an old friend of Fang’s, a white musician with the long hair, grizzled face, and slender, angular body of a hippie who was almost aging gracefully. I had only met “Joe” once or twice before, so I was unfamiliar with his politics and worldview. We had a fairly wide-ranging and, quite frankly, mostly forgettable conversation in our brief visit, but the closing bit of it made quite an impression. Joe told us that “when the n*****s rise up,” we should join him and his wife in their house because they had both bolt-action and semiautomatic rifles, and their house occupied slightly higher ground that the rest of town.

Because this man used to be one of Fang’s best friends, and because I didn’t want to expose my three-year-old to any more such talk, I confess that instead of confronting Joe about his frankly delusional prediction I performed a rather lame “Oh my! Look at the time!” retreat.

Still, the exchange opened my eyes to a white fantasy of fighting off, with deadly force, darker-skinned trespassers or invaders. I certainly was no stranger to whites’ skewed views of African Americans’ capacity for violence. After all, I am white, and even in “polite company,” some white people let certain politically incorrect views slip from their lips. I also had studied racism on a more intellectual level, as while I was a student at UC Davis, I had the good fortune to study with and T.A. for one of the founders of the field of “whiteness studies”–or, as practitioners sometimes prefer to call it, “the critical inquiry of whiteness”–the late Ruth Frankenberg. And indeed, conversations about white privilege striated my graduate courses in cultural studies and were reinforced in the gender studies seminars I pursued. (I was the only person in my graduate cohort whom most Americans would consider white, so as you might imagine I was often placed in an interesting subject position, though as I said in the post introducing this series, I actually feel my whiteness most acutely when I’m surrounded by white people rather than when I’m the “only.”)

So when I heard of the Newtown shooting, and it emerged (unsurprisingly) that the perpetrator was a white man, I found myself making sense of the shooting in terms of whiteness and masculinity, and trying to triangulate among race, class, gender, religion, and partisan politics. There is, of course, a large body of academic research and criminal and social justice work on masculinity and violence, but Newtown prodded me to look at how mainstream Americans, and particularly white Americans, perceive (or fail to perceive) patterns of white masculinity and gun violence.

Fortunately, I wasn’t alone in my observation and reflection.

At the Huffington Post, Michael Kimmel and Cliff Leek dared to address the white elephant in the room. I found these two paragraphs from their post especially incisive about the race and gender of victims of mass shootings and their perpetrators:

Newtown is a white, upper and upper-middle-class suburb. Think of the way we are describing those beautiful children — “angels” and “innocent” — which they surely were. Now imagine if the shooting had taken place in an inner city school in Philadelphia, Newark, Compton, or Harlem. Would we be using words like “angels”? We don’t know the answer, but it’s worth asking the question. It is telling though that we do not see a national outcry over the far too frequent deaths of black and brown skinned angels in our nation’s inner cities.

Now let’s talk about the race and class of the shooter. In the last 30 years 90% of shootings at elementary and high schools in the U.S. have been perpetrated by young white men. And, 80% of the 13 mass murders perpetrated by individuals aged 20 or under in the last 30 years have also been committed by white men. There is clearly something happening here that is not only tied to gender, but also to race.

Immediately following the crime in Newtown, the tireless Chauncey DeVega delved deeper into this cultural crisis in a series of thoughtful posts (and now an interview with Historiann as well) interrogating the role of white masculinity in mass shootings in the U.S.

In response to Andrew O’Hehir’s post “How America’s toxic culture breeds mass murder,” in which O’Hehir emphasized that “America has an major angry-man problem,” DeVega elaborated on the fact that the U.S. has an angry white man problem:

Andrew’s oversight is a common one in a society (and among the pundit classes) where whiteness is taken to be a condition of both normality and invisibility. Whiteness has social power precisely because it goes unnamed. To be White in American society, with its long history of white racism and other inequalities that are structured around the colorline, is to be considered “normal.”

Ultimately, whiteness is the ability to be an unmarked individual whose actions do not reflect on your racial group. Consequently, white men who kill are just individuals who kill; black and brown folks who kill and commit other crimes are exhibiting behaviors which reflect on their “race” and “culture.”

To point. American politics and culture are obsessed with narratives that link race and crime.

DeVega then brings it home:

Given the cultural scripts that inexorably relate crime to race, one would think that white people, and white men in particular, would be the focus of similar narratives. White men are the majority of domestic terrorists in the United States. White men commit the most serial murders and child rapes. White men comprise the vast majority of those accused of treason. White men destroyed the country’s economy and financial sector.

And white men have committed 70 percent of the mass shooting murders in the United States as sourced from this piece in Mother Jones. By comparison, white men are approximately 30 percent of the population. They comprise more than twice their percentage among mass shooters. Yet, there is no “national conversation” on the matter. The silence is deafening.

DeVega continued to break the silence on his blog and elsewhere. At Alternet, he wrote

If Adam Lanza was an Arab American with one of those “Muslim sounding” names, then today’s script would be quite different. Questions of “terrorism” would loom large: it would be the default frame for reading the Connecticut school shooting. In all, the United States has a post 9/11 hangover where a moment of national trauma made one group of Americans a perpetual Other.

A person of color who happens to be of Arab descent, and who is Muslim by chosen faith or birth, is not allowed to be a deranged individual who made a choice to kill dozens of people. His or her identity and personhood is one that is “politicized” by default in the West. As such, all actions, however random or outliers, are taken as representative of some type of collective identity, one where terrorism is an inexorable part of its character.

It’s important to note that despite these observations, DeVega isn’t calling for racial profiling. Rather, he’s pointing out the hypocrisy of conservative white men calling for continual surveillance and profiling of particular groups of people because someone who happens to fall into a their demographic (Muslim immigrant, in this example) commits a rare but heinous crime. These conservatives are taken aback by the merest suggestion that there may be a pattern of white male gun violence–and especially of mass shootings–and refuse to believe that there may be fatal flaws in the ways white families raise white boys and men. God forbid anyone suggest as a nation we must examine the sources of that violence and the ways that white Americans’ easy access to guns amplifies violence. (DeVega elaborates on some of these pathologies in another post.)

DeVega is more eloquent on the subject:

In all, I am legitimately taken aback by the sincerity of the pain and offense at the idea that white men could be experts at committing singular types of crime in America.

Moreover, in surveying the comments and reactions to my (and other) essays about Adam Lanza, white masculinity, and gun violence, there is a tone of real hurt:

White Masculinity, like Whiteness, imagines itself as normal, innocent, and benign. The very premise that the intersection of those identities could result in socially maladaptive and violent behavior which is evil, and yes I use that term intentionally, is rejected by those deeply invested in a particularly conservative and reactionary type of White Masculinity, as something impossible. To even introduce such an idea is anathema to their universe. The language is verboten. The Other is suspect until proven otherwise; “real Americans” as “good people” are to be judged by precisely the opposite premise.

DeVega ventured into what liberals certainly perceive as one heart of darkness in the large subculture that perpetuates such myths: a forum frequented by owners and fans of the AR-15 assault rifle. Included among his observations is this one explicitly connecting white nationalism and gun fandom:

These people hate President Obama. Although, he has done nothing to strengthen gun control laws he is evil incarnate. Much of the rage is talking point Right-wing claptrap. Nonetheless, the anger is real. There is also no small amount of white identity politics on display with its obligatory hostility to people of color. At present, conservatism and racism have overlapped in the United States. The survivalist and militia crowd have long been an organ of white nationalism. As such, the overlap of white racial resentment and extreme gun culture is not a surprise. This is especially true given the role of guns in maintaining white power in a country that for centuries was a Constitutionally mandated formal Racial State.

[. . .]

I would not go so far as to say this speech is treasonous or seditious–although it is mighty close–but given the political environment of the United States, and the routine use of eliminationist rhetoric by the Right-wing media against anyone not white, male, heterosexual, Christian, middle class, and conservative, one would have to be a fool to not be concerned about a bunch of heavily armed people that imagine themselves as uber patriots and 21st century guardians of “democracy.”

Some numerical correlations

Frightening indeed. And if you’re not persuaded by DeVega’s brand of cultural analysis, then let’s go quantitative, shall we? Writing at The Atlantic, Richard Florida reports on a statistical analysis of gun ownership, politics, and gun violence by state. His findings suggest common assumptions about the causes of gun violence are incorrect.

We found no statistical association between gun deaths and mental illness or stress levels. We also found no association between gun violence and the proportion of neurotic personalities. . . . We found no association between illegal drug use and death from gun violence at the state level.

[. . .]

What about politics? It’s hard to quantify political rhetoric, but we can distinguish blue from red states. Taking the voting patterns from the 2008 presidential election, we found a striking pattern: Firearm-related deaths were positively associated with states that voted for McCain (.66) and negatively associated with states that voted for Obama (-.66). Though this association is likely to infuriate many people, the statistics are unmistakable. Partisan affiliations alone cannot explain them; most likely they stem from two broader, underlying factors—the economic and employment makeup of the states and their policies toward guns and gun ownership.

[. . .]

And for all the terrifying talk about violence-prone immigrants, states with more immigrants have lower levels of gun-related deaths (the correlation between the two being -.34).

Florida also reports that states that with stricter gun control legislation have fewer firearm deaths. “We find,” he writes, “substantial negative correlations between firearm deaths and states that ban assault weapons (-.45), require trigger locks (-.42), and mandate safe storage requirements for guns (-.48).” Definitely click through to see the map highlighting the number of deaths and injuries by firearms per state per 100,000 persons. I’d love to see the same map on the county level, with racial and ethnic demographics overlaid on it. After all, a recent Pew Research Center study (PDF) underscored that it is white, politically conservative Protestant men who are most interested in preserving easy access to guns. (Alas, my GIS skills are not such that I can produce such a map, but if you know of one, kindly leave a link in the comments.)

A caveat

By writing this post, I’m not by any means trying to trace all gun violence somehow to white conservative men, or to pathologize white American men more generally. As a country, we definitely need also to consider the rates of black-on-black violence, as while the rates of African Americans dying by or committing homicide declined in the 1990s, they leveled off shortly before 2000, and they remain significantly higher than rates among whites. (Though as the statistics at this link sent by my friend Dave show, homicide-by-gun victims are just about as likely to be white as black, and white offenders are more likely than black offenders to kill multiple people.) And although Richard Florida and others have over the past couple of weeks emphasized that mental illness is not a large factor in gun homicides, we still need to address the intersection of mental illness and gun availability, as it leads too often to suicide.

This is a profoundly complicated issue, and I know that in this series of posts, I’m only going to be bringing small pieces of it to light. They are pieces, however, that I feel are going largely unremarked upon in mainstream American discourse.

Readers, I’m curious about what you think.

I know some of my readers are gun owners, others are politically conservative, and I suspect many (if not the vast majority) are white. Regardless of your subject position, what are your thoughts? Are you as persuaded as I am–by DeVega’s posts, your own experiences, crime statistics, or other sources–that we must consider white masculinity as a major factor when we discuss gun violence in the U.S., and in particular when the subject is massacres? If you don’t see white masculinity as a factor in these kinds of crimes, what cultural or demographic forces do you think are more forcefully at work?

As this is an issue that raises hackles, I encourage us to be especially respectful if a conversation emerges in the comments below.

Gratitude

I am so thankful for my little family this week. Lucas has been a great gofer and has (mostly) kept himself entertained. (He has been making Valentine’s Day cards for the extended family and sewing little felt pouches adorned with hearts as gifts.) And Fang has gone above and beyond the requirements of those in-sickness-and-in-health vows he took a decade ago.

He has taken me to urgent care twice, fetched escalating prescriptions of antibiotics, fixed meals for the boy, kept Lucas entertained with reading and guitar lessons and movies, and more–all while meeting the multiple deadlines of a newspaperman (his preferred title). I am so very fortunate to have such a caring, thoughtful, capable spouse–especially since I suspect he knew the job wouldn’t be easy when he signed up for it.

Thanks so much, Sweetie. Here’s to a healthier new year!

* “Milk Truckers” is one of my fave WPA posters of all time. Glad I finally found an excuse to use it.

Themes for 2013: Completion, then space

A couple weeks with pneumonia means a lot of time propped up on the couch. Once the novelty of watching way too much TV wore off, my eyes wandered to the books on the shelves, cobwebs in high places, dust on the baseboards, Christmas tree needles embedded in the living room rug.

Before I could even stand up confidently, I was mentally Swiffering the ceiling corners and telekinetically weeding books from the shelves, sorting them into donations and those that should be in my campus office. I ignored my usual work-oriented task list in Dropbox and scrawled a five-page to-do list in one of the far too many blank journals and sketchbooks that have accumulated in my home office. I color-coded tasks by how sedentary they were, assigning each (perhaps optimistically) to a day of this week. And then–because I couldn’t bear to stream another episode of 30 Rock from Netflix–I found myself accomplishing the lowest-energy of these tasks.

I have to remind myself to slow down, that if I push myself too hard I could relapse further into the pneumonia, but between the steroids and the antibiotics, I’m feeling much better. Hell, I even dusted a few shelves today–without descending into a coughing fit–as I carefully lowered extraneous books into boxes.

I’m enjoying having cleared that space, however small it may be. And I’m realizing that the cramped nature of my life extends beyond my shelves; having too many irons in too many fires can have a real impact on my health. At the same time, I’m committed to collaborations I enjoy and I’m loath to abandon.

So while I’ve spent the last couple of years here trying to grow professional and personal roots–one of my themes has been groundedness–I now need to focus on bringing projects to completion. Completion will help me with my case for tenure (I anticipate submitting my tenure portfolio in fall 2014), but perhaps more importantly it also will allow me much-needed space for health and wellness. Once I complete the various article-length writing projects and launch a couple of digital projects into the community, I expect to finally have the time and space to focus adequately on my well-being and on the book I’ve been brewing.

It’s fitting, then, that I spent the last day of 2012 alternating between rest and completing small tasks I should have crossed off my list long ago. Here’s to a new year of completion and spaciousness and health.

What are your hopes and plans for the new year?

Wheeeeee!

Just when I thought I was out of the pneumoniac woods, it ends up it’s antibiotic-resistant pneumonia.

I’m now on a new antibiotic, one that the physician’s assistant assures me will “kill anything inside” me.* Yay?

*Just looked up the antibiotic–it’s also used to treat meningitis, anthrax, tuberculosis, and plague. Fun times.

Blog, interrupted

I had the best intentions of exploring gun violence in the U.S. in a series of posts here–and I still will.

However, the day after finals ended, I came down with bacterial pneumonia. I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone. As soon as I have fully recovered, I’m getting the damn vaccine, as this is case o’ pneumonia #2 since moving to Boise–after never having had it previously, and having had the flu shot religiously, which is supposed to dramatically reduce the changes of contracting the ol’ lung fever.

I’ve come out of this incident with a key bit of knowledge (which you’d think an asthmatic would have absorbed long ago): Normal blood oxygen levels = VERY GOOD. Blood oxygen levels in the mid-80s = BAD. (In fact, so bad that, combined with the other symptoms, the doctor said drily, “A chest x-ray is not indicated.”)

I hope everyone’s holidays have been excellent. Here’s to better health in 2013!

Have a celebratory drink for me, eh? I’m on antibiotics.

Not-so-random bullets

Back in my cultural studies grad school days, I heard frequent exhortations by left-leaning professors that the classroom is inherently a political space and we should be open about our own political stances. About half of the faculty I heard this from seemed to be saying that students’ own beliefs need challenging (and broadening), while the other half seemed to suggest that only if we come clean about our own political commitments can we be considered good teachers. After all, we can’t go about criticizing white male [philosophers, scientists, historians, curators, politicians] for adopting a “view from nowhere” if we ourselves aren’t situating our knowledge or, in the case of teachers, our presentation of allegedly objective knowledge, in the context of our cultural habits, beliefs, and values.

Here in Idaho, many of my students aren’t especially eager to hear my feminist perspective on issues. (On several occasions, I have had male students name the “worst professors” in my college as the ones I’m guessing are most likely to present an overtly feminist perspective on the past and present.) I deliver this same perspective in my courses, I suspect, but it’s much more moderated than it was when I was standing in the front of California classrooms. I still present the same ideas, but I’m more likely to counterbalance them with ideas to which my most conservative students will be more sympathetic.

So, for example, in the first “half” of the history survey, I have them read Clarence Walker’s Mongrel Nation and we discuss it for a couple of days, but I also have them look at the Thomas Jefferson Heritage Society’s Scholars Commission report on l’affaire Hemings. I emphasize slavery and gender and a relatively countercultural view of U.S. history throughout the semester, and then we read the Texas state standards for U.S. history. For me, it’s not a matter of perfect balance–I do usually take a stance at the end of each activity–but of challenging students from both sides of the political spectrum with inconvenient facts. While my students are WTF?ing about why Jefferson isn’t more prominent and asking if the Texas standards aren’t some kind of conspiracy by the extreme right, I ask them why they don’t know more about “Benjamin Rush, John Hancock, John Jay, John Witherspoon, John Peter Muhlenberg, Charles Carroll, and Jonathan Trumbull Sr.”–the founding fathers deemed most significant by the Texas state board. Could that be some kind of conspiracy? (Cue sound of minds being blown.) Such moments open good discussions about how all textbook historiography is political and that history gets practiced by all kinds of people for all kinds of ends. (Example: Why are so many of the students in my class required to take the wide-ranging survey course instead of courses that would allow them greater space to examine issues in depth?)

My point is this: I make clear to my students that most of them are going to consider me a flaming liberal/crazy Californian/just the type of person who is ruining Idaho. But then I win their trust, and they usually consider my position.

I owe a good deal of credit to Fang; as I was maturing out of my early-twenties jejeunosity, he modeled the whole walking-a-mile-in-someone-else’s-perspective thing exceptionally well. And he’s still really, really good at it.

I like to think I can be, too.

But there are a couple of issues where I just can’t moderate myself–as anyone who has seen my FB postings the last couple of days can attest.

Gun violence is one of those.

And yet I moved from a state (California) that scored 81 on the Brady Campaign’s scorecard to one that earned–wait for it–a 2. And not surprisingly (to me, at least), Idaho is also one of the states where people are more likely to kill themselves or others with a gun, accidentally or intentionally. (Not surprisingly, the map of that data bears a strong resemblance to the 2012 presidential election results.)

People on all sides of the gun control debate (and isn’t that all of us?) let emotion control their beliefs and habits. (Fear, mostly.) As we try to figure out how to feel more secure despite this fear, we draw on whatever personal experience we have, whether that be first-hand experience with guns or the cultural context in which we came to know about gun violence.

Over the next several days, I’m going to share a lot of links I’ve been collecting about gun violence, gun control, and gun ownership. There’s going to be a lot of data and logic, and much of it is going to–surprise!–point out that more regulation of guns is a good idea. There will also be a good deal of personal reflection–this is my personal/academic blog, after all, so the posts are all but required to aspire to public intellectualism before devolving into maudlin solipsism. First, though, I want to don my good-teacher cardigan and position myself vis-à-vis this subject. Here are a few not-so-random, er, bullets that may not yet seem to all be related to the same theme:

- The first time I saw a gun in person, it was my grandfather’s service revolver. He was a retired police officer, and he told me I should never, ever touch a handgun. (In the same room–my grandparents’ bedroom–many years later, as he lay dying, he would tell me to stay away from alcohol, drugs, and fast women. He died when I was only 15 years old, but in later years I learned from my grandmother that he was sort of a walking cautionary tale.)

- My grandmother disposed of the handgun almost immediately after Grandpa died. Very shortly thereafter, a mentally ill man who had gone off his meds tried to punch through the glass on Grandma’s front door. He wanted to injure the home’s inhabitants, and yes, he had known there was a gun not far from the front door when Grandpa was alive. The first thing Grandma said to me after the incident was that she was so glad she had gotten rid of that gun.

- I grew up in a household free of guns.

- When I was in high school, I regularly heard gunshots in the neighborhood as I was waiting to be picked up from orchestra practice on Wednesday nights.

- There were many, many gang members in my high school.

- I was in high school in Long Beach during the Los Angeles riots. I watched the violence unfold on TV at night, then drove to school the next morning to find the occasional building burned down between my house and the school. Never, however, did I feel unsafe.

- My senior year, I wrote the obituary page in my high school yearbook.

- When I was a student there, my high school was 20 percent white. There were 50+ languages spoken at home by its students.

- I feel most white not when I’m the only white person in a crowd, but when I’m in a crowd full of white people. I’ve never felt more conscious of my whiteness than I have in Idaho.

- The only time I feared for my safety sufficiently that I went straight to a police station was when I was pursued on a bike by a white man in Fredericksburg, Virginia. (I was 18.)

- I have been a vegetarian for more than two decades, and I aspire to be vegan. When I really commit myself I can be vegan for weeks on end, and I look and feel awesome.

- I have a history of serious depression, and I’m not the only one in my home who struggles with it.

Connecticut

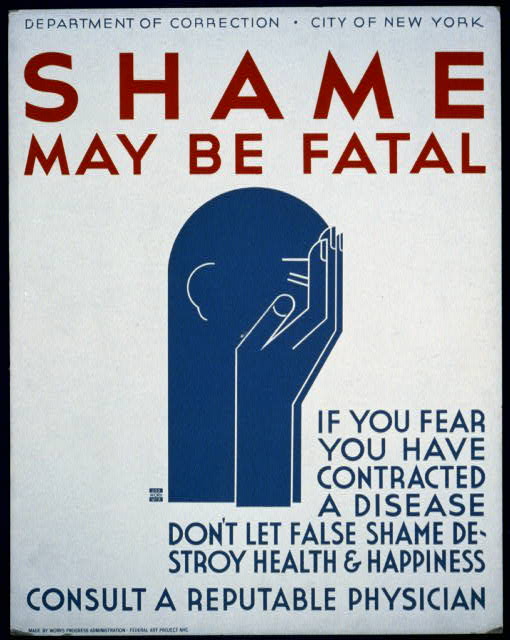

Pay attention to the number on the right.

And please donate to the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence if you are so moved.

A semester full of crises

Not for me. For my students.

Let’s make an inventory, shall we?

- PTSD

- debilitating illness

- debilitating depression

- debilitating anxiety

- at least one jailed spouse

- crises of single parenting

- job loss

- family members at death’s door

- friends murdered

- friends committing suicide

- friends on suicide watch

- friends injured or killed in horrible accidents

- debilitating migraines

And I know I’m forgetting something. It’s been a long semester.

At midsemester, I came out to students as a depressive, as there still seems to be here (especially among veterans) a stigma around mental illness. I shared, briefly, my struggles with depression, and I emphasized that things got better when I sought help. Perhaps it’s not surprising, then, that I’ve had a series of students in my office since then.

Their challenges are tremendous. I don’t have to solve their problems; I merely serve as a listening ear–as someone who demonstrates she cares about them when they feel alone–for a few minutes. Fortunately, Boise State has a program to which I can report students who are distressed, and the response time is great.

I’ve been sharing with these students something I wish had been reinforced for me when I was a student. It’s a brief list of priorities:

1. Self-care

2. Care of family and friends

. . .and only then. . .

3. Coursework

Perspective! It’s useful. Pass it on.