Pay attention to the number on the right.

And please donate to the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence if you are so moved.

Pay attention to the number on the right.

And please donate to the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence if you are so moved.

Not for me. For my students.

Let’s make an inventory, shall we?

And I know I’m forgetting something. It’s been a long semester.

At midsemester, I came out to students as a depressive, as there still seems to be here (especially among veterans) a stigma around mental illness. I shared, briefly, my struggles with depression, and I emphasized that things got better when I sought help. Perhaps it’s not surprising, then, that I’ve had a series of students in my office since then.

Their challenges are tremendous. I don’t have to solve their problems; I merely serve as a listening ear–as someone who demonstrates she cares about them when they feel alone–for a few minutes. Fortunately, Boise State has a program to which I can report students who are distressed, and the response time is great.

I’ve been sharing with these students something I wish had been reinforced for me when I was a student. It’s a brief list of priorities:

1. Self-care

2. Care of family and friends

. . .and only then. . .

3. Coursework

Perspective! It’s useful. Pass it on.

The guppies and I had an understanding, and it involved cannibalizing their young.

Let’s rewind a couple of months:

As a reward for earning his yellow belt in Taekwondo, Fang promised Lucas a fish tank. Not just goldfish, Fang emphasized—real fish.

I think Lucas may have had visions of a 50-gallon saltwater tank filled with yellow tangs and angelfish, live coral and maybe a small eel. Something you’d see in a doctor’s office waiting room. Maybe Fang did, too, not realizing the cost and maintenance involved in such a set-up.

In the end, it fell to me to set up the fish tank. My parents kicked in a gift card to a chain pet store as a birthday gift to Lucas so we could get the tank, and they sent along as well some aquarium decorations. Fang and I purchased all the other little things that come with setting up a new tank: dechlorinator, living plants, gravel, pump filters, water test kits, freshwater aquarium salt, siphon, starter bacteria, and more. I printed out a fish compatibility chart and explained to Lucas that the 10-gallon tank could hold only five or six fish, and that most of the fish for beginners liked to school, so it’s likely we’d be able to get only one or two types of fish.

We set up the tank and let it settle for a few days, knowing that we were going to cycle the tank with fish. The water’s pH was very high, so we opted for guppies, which apparently can thrive in high-pH water. I read more than I ever dreamed I might about Poecilia reticulata. At this point in our adventure I was confident I could write a damn good literature review, entitled “Advice to New Freshwater Home Aquarists, with Special Attention to Rising Ammonia Concentrations.”

Guppy enthusiasts remain divided as to the ideal female: male ratio. The textbook answer is two females to each male, but vast anecdotal evidence on the interwebs suggests that it really all comes down to the temperaments of the individual guppies. Still, patterns emerged: If you have only females, one will likely become an alpha and abuse the others. If you go the male route, and one male guppy is a total asshole, then he’s going to harass any guppy, regardless of sex. My ever-vaster reading made clear to me that guppy tending falls somewhere, though I wasn’t sure exactly where, on the spectrum of “Great Introduction to the Aquarium Hobby” and “Total Crapshoot, Kids.”

Need I point out that I wasn’t interested in getting into the business of fancy guppy breeding? And that I didn’t want to have to console a seven-year-old when the adult guppies devoured the babies? I explained to Lucas that it would get Darwinian pretty damn quickly in the tank—meaning I enthused, “Guppies make their own food!” Lucas said, with far too much sangfroid for my taste, that he was “okay with blood.”

In the end, we went with the fish store employee’s advice to get two females and one male, though she confessed she herself had three males and one female that apparently never became pregnant. We brought the fish home and while at home, I did little but fret about guppies. (Alas, I inherited, through nature and nurture, a visceral aversion to animal suffering, no matter how small-brained or short-lived the creature.)

My Facebook updates quickly descended into guppy management angst. I had committed to twice-daily partial water changes and lots and lots of water testing.

The guppies, meanwhile, had committed to procreation. I’m pretty sure one of the females was pregnant before we reached home.

Soon it became evident that, promised guppy cannibalism aside, Lucas expected to keep some of the baby fish. I procured a second, smaller tank.

A few weeks later, Lucas was excited to see the teeny tiny guppy fry in the tank, and encouraged me to scoop them out. This process has repeated itself several times, so that we now have about 20 tiny fish in the nursery tank–waaaaaaay too many for an aquarium that size.

From my reading, female guppies birth between two and 200 fish at a time. Wikipedia reports, “Guppies have the ability to store sperm up to a year, so the females can give birth many times without depending on the presence of a male.” We have two females. You do the math.

We could be talking about a lot of guppies. Yet we have seen fry swimming around in the tank, then suddenly they were gone. In fact, Lucas has had the pleasure of seeing one of the females eat a newborn guppy.

I figured, then, that once we had found homes for, oh, 18 of the fry in the secondary tank, we would have reached guppy detente: Guppies are born. Guppies get eaten.

Why, then, did this week the guppies break our social contract? There are four fry swimming around the tank, and they’ve been there for about 48 hours.

Anyone want some guppies?

UPDATE: I just went into the kitchen and discovered THIRTY guppy fry.

(This is another über-post. I’ve been feeling some bloggers’ block lately, and this is my attempt to just get The Big Issues out there so I can refocus.)

Since I came to Boise, I have thrived professionally. (This isn’t to say that I’ve garnered major grants or become a publishing machine, but I’m establishing a strong foundation for whatever comes next. My departmental mentoring committee has assured me that I’ve checked all the key boxes for tenure, though I still have two years left on that clock.)

I can attribute this phenomenon primarily to a few things:

I am grateful the stars have aligned in such a way. I’m involved in all kinds of interesting collaborations and initiatives. If everything continues as it is now, I’d be content to spend the rest of my career here.

(You knew there was a “but” coming, yes?)

The people I brought with me to Boise are, for reasons I won’t go into here but which aren’t of their own making, not thriving to the same extent I am. It’s becoming ever clearer that it might be beneficial for us (all of us, not just Fang and Lucas) to be closer to family, which ideally means Southern California, where just about all my family lives in the same zip code, and where a pillar of Fang’s family also resides.

Am I actively searching for a job? Did I even look at the academic job listings this fall? Have I applied for any jobs? No.

Consider this post a me-putting-it-out-there-to-the-universe that within the next 5-7 years I might like to relocate. I have some projects I want to finish, or at least see take on lives of their own, and Lucas has expressed a desire to move to California when he’s finished at his current school. (Is this an announcement that I’m leaving Boise State? Not at all. In fact, it’s unlikely I will, as no one in my department has left eagerly (retirees possibly excepted) in living memory. Still, I’m open to change.)

I landed on the tenure track at a pivotal moment in higher education–by which I mean that I can see many universities, including my institution, beginning to pivot away from an instructional and academic model that interests me to one that decidedly doesn’t. I feel compelled to stay long enough to discourage such pivoting–or, rather, to encourage the institution to pursue a smarter trajectory.

For example, there’s something chafing about being in a college of social sciences at a moment of where the larger university is emphasizing analytics. Suddenly we’re having to input all our faculty activities into a database that–because it’s called “Digital Measures”–I suspect has some kind of algorithm, programmed by the university, that spits out a quantitative assessment of faculty work. As a humanist, this is problematic on a number of levels–first, as a junior faculty member doing unconventional work, my efforts are especially resistant to quantification. I’m having a hell of a time fitting my work into any of the drop-down categories, and I don’t know how to handle the first/second/third author thing on conference panels where everyone contributes equally. Second, and perhaps more obviously, I have a deep-seated philosophical resistance to such quantifying measures, a resistance that goes way beyond my own puzzling situation.

On the instructional side of this pivot, I’m skeptical, nay critical, of MOOCs—or of any online instructional model that assumes students should sit through lectures to learn content that can be tested using multiple-choice exams. Universities seeking to scale the delivery of content are headed in the wrong direction; they should be looking instead to both broaden and deepen student participation in critical and creative thinking. Massive courses, especially those driven by students’ content mastery, are not the way to cultivate an intelligent and engaged citizenry.

Which brings me to a related point. . .

I have launched myself into a paradoxical career space. I was hired as a public historian, although I wouldn’t necessarily have considered myself one of that species prior to my arrival here. The further I explore public history theory and practice, the more I find myself emphasizing a vision of historical practice that pretty much goes against what typically happens in academic history, which suggests maybe the academy isn’t the best place for me, philosophically, though it certain is the best place for me temperamentally. (Again, a subject for another post.) In brief, I believe that we’re at a technological and cultural moment when it’s silly to continue teaching (in K-16) the same sweeping courses (the Pleistocene to 1877 survey, for example), and that it’s more important to teach students to be thoughtful citizens of the republic–by which I mean that we should be having students do considerably more primary source discovery and interpretation than I’ve seen in the classroom (here and elsewhere). (I’ve heard a lot of lip service paid to such pedagogical practice, but have observed insufficient implementation.)

We should be emphasizing the necessity not of knowing history well, but of doing history well. For me, “public history” comprises not merely history undertaken by professional historians for a public audience, but rather the ways the public undertakes and understands history. With such a perspective, it’s kind of a no-brainer that I need to teach my students how to do history well–which means more that content mastery or writing a good essay in response to texts we have read in class.

I have colleagues (and readers, I’m certain) who believe doing history well means having a foundation in the facts (for example, the canonical history portrayed in U.S. history survey textbooks). I have to ask: How’s that model been working out over the past century or so, in terms of the historical and scientific literacy of the American public?

I want to be part of an educational solution, and I’m not certain I can do that most effectively from within the undergraduate (or graduate) history classroom.

One of my favorite career-finding books, and one I recommend regularly to my students, is Barbara Sher’s Refuse to Choose. In it, she describes “scanners,” bright people who are simultaneously and/or serially interested in diverse and sometimes divergent subjects and careers. She categorizes scanners according to their intellectual and behavioral patterns, then details the possibilities and pitfalls that accompany life as a scanner. As someone with an M.A. in writing poetry, a Ph.D. in cultural studies, a tenure-track position in a history department, and a professional background that is a crazy quilt of journalism, educational publishing, arts marketing, development communications, hands-on science learning, exhibition development, museum studies, academic technology, and higher ed pedagogy, I definitely identify with Sher’s taxonomy of scanners. I see many paths available to me, as an academic, employee, or entrepreneur.

Instead of being excited, however, I feel stuck. That’s largely because financially, moving to Boise was a mistake. Not only did I take a big salary hit that wasn’t offset by a diminished cost of living, but Fang also had his hours cut and had to become an independent contractor instead of an employee, which means he both took a pay cut and has to pay self-employment taxes. We’ve been dipping into our meager reserves more regularly than I’m comfortable admitting. I’m very conscious, then, that my next move must be financially remunerative in a big way.

That stuckness also comes from being overcommitted (as academics are wont to be, but I’m perhaps more entangled in projects and programs than is considered normal in these parts). It means I don’t have a lot of spare time to explore reasonable new paths. I hereby declare 2013, then, as the Year of Letting Things Go.

Unfortunately, “letting things go” doesn’t mean just kicking back–in fact, at first it might mean kicking everything up a notch. So, what might “letting things go” look like for me?

What are the benefits of letting things go by reinvesting in these projects before divesting myself of them?

What about you, readers and friends? What’s keeping you occupied these days, and what are your plans for moving forward, in 2013 and beyond?

Thanks to wildfires in Idaho, Oregon, Nevada, and even California, the Treasure Valley, where Boise lies, is shrouded this week in dense smoke. The haze obscures the mountains in all directions, and it even makes it difficult to see the local foothills. We can not only see and smell the air–we can taste it. Our latest houseguest joked that the tomatoes harvested from our garden come pre-smoked.

This haze, coupled with the heat—we’ve had highs of 100 degrees or so for the past couple weeks—means that my final couple weeks of summer, which I traditionally aim to spend puttering in the garden, reading on the shady patio, and taking long morning walks with the dog before the day gets too hot, have been, and will continue to be, spent indoors. I’m one of the lucky folks to fall into the “sensitive groups” mentioned in air quality reports, so I especially resent being taken hostage by the smoke, colorful sunsets be damned.

While I’m most plagued by the literal haze, I must acknowledge the equally dense metaphorical haze that has settled over our household.

I’m not super comfortable with uncertainty, but Fang is even less tolerant of it, and right now our vision of the future is hazy at best.

Fang is going back to school for the first time in 32 years—very part time, as a history major—but he also is taking on a half-time job in the History department office as front-desk staff. He’s going to continue to do his freelance graphic, web design, and photography work, but he (well, we) decided he needed to get out of the house more often.

Still, Fang, ever the optimist, sees the new job as the beginning of the end of his life. He feels—and who can blame him?—that at age 50, he shouldn’t be accepting jobs that pay not much more than minimum wage. Plus, it doesn’t help that we’re never certain when work from his biggest freelance clients will dry up—such is the danger of working for clients in the newspaper industry, where Fang’s expertise (and freelance workload) is strongest. Too much uncertainty! Too much change!*

Last year, he finished a novel, but because it’s long—666 pages, to be exact—he’s had a hard time persuading busy friends and family to read it and offer feedback. I made it all the way through, copyediting and offering suggestions, and—shhh! don’t tell him, because he doesn’t like to talk about it—I’m doing another read-through in the hopes of getting it to the point where we can talk to an editor or agent, or we can publish it on Kindle and print on demand. Because nobody else bothered to read it, though, he’s feeling very much as if his dream of being a writer is dead.

That’s disheartening to me, because (and maybe I am biased here) he’s one of the sharpest writers I know. At the same time, some very smart folks I know who read his blog have told me, completely unprovoked, that it’s one of their favorites. I’m hoping the new job, with its regular schedule and its human interface, will remind him that he can make—and has been making—valuable contributions in any number of social, cultural, and political spheres.

In the meantime, if you do read Fang’s blog, do me a favor and leave a comment from time to time, OK? You needn’t praise him, of course, but comments let him know someone is reading and appreciates what he’s doing. Maybe it will help clear the haze around here.

Thanks, and I’ll let you know when his novel is available.

* Fang once explained, “It’s only a rut if you’re looking down on it. If you’re in it, it’s a groove.”

(Source; h/t Audrey Watters)

Last time I checked, Boise State’s 4-year graduation rate was 8 percent.*

No, that’s not a typo. And its 6-year graduation rate hovers at 26 percent, with an overall graduation rate of 27 percent. One could quibble and point out that transfer students aren’t traditionally included in the university’s graduation rate calculations, but even if we’re only counting students who begin their college careers at Boise State, 8 and 26 percent graduation rates are pretty damn astounding, and not in a good way.

Not surprisingly, the university is feeling a good deal of pressure from the State Board of Education and the legislature to improve these graduation rates. In fact, the State Board has set an ambitious goal: 60 percent of Idahoans should have a college degree or some kind of post-secondary certificate by 2020. (Note the language of the bullet points on the State Board’s College Completion Idaho page–it’s very much about improving efficiency and quantity of post-secondary completion rates, not about quality of education.)

I’m told** by folks allegedly in the know about such things that the completion rate for online courses at Boise State is lower than the completion rate for face-to-face courses.

I’m no mathematician, but it seems to me that’s a pretty simple equation:

already low graduation rates + low completion rates for online courses ≠

improved graduation rates.

(Yes, I have written about this before.)

Image by Shane Lin, and used under a Creative Commons license

I haven’t commented here on the Teresa Sullivan resignation-and-reappointment scandal at UVA, and I wasn’t planning on it. But plans change, yes?

In case you didn’t watch the whole ugly mess unfold, that link to the Washington Post provides a play-by-play of what the newspaper terms “18 days of leadership crisis.” In brief, it appears the UVA president was pressured to resign because the university’s Board of Visitors believed she wasn’t leading the university down the right path to online education. Specifically, their e-mail exchanges show they referred to an article in the Wall Street Journal about the coming changes in higher ed. That op-ed enthusiastically states:

Moreover, colleges and universities, whatever their status, do not need to put a professor in every classroom. One Nobel laureate can literally teach a million students, and for a very reasonable tuition price. Online education will lead to the substitution of technology (which is cheap) for labor (which is expensive)—as has happened in every other industry—making schools much more productive.

While that may seem like a utopian future to the WSJ contributors–and I think they and I have very different definitions of “productive”–it sounds more dirge-like to those of us who work in actual classrooms with non-hypothetical students.

The e-mails sent among the Board of Visitors folks make for enlightening and disheartening reading. UVA professor Siva Vaidhyanathan captures their essence when he writes, “In the 21st century, robber barons try to usurp control of established public universities to impose their will via comical management jargon and massive application of ego and hubris.” You should click through to read his entire post at Slate, but this passage bears highlighting:

The biggest challenge facing higher education is market-based myopia. Wealthy board members, echoing the politicians who appointed them (after massive campaign donations) too often believe that universities should be run like businesses, despite the poor record of most actual businesses in human history.

Universities do not have “business models.” They have complementary missions of teaching, research, and public service. Yet such leaders think of universities as a collection of market transactions, instead of a dynamic (I said it) tapestry of creativity, experimentation, rigorous thought, preservation, recreation, vision, critical debate, contemplative spaces, powerful information sources, invention, and immeasurable human capital.

In a follow-up post, Vaidhyanathan writes, “Dragas demanded top-down control and a rapid transition to a consumer model of diploma generation and online content distribution. She wished to pare down the subjects of inquiry to those that demonstrate clear undergraduate demand and yield marketable skills.”

As many faculty at UVA and elsewhere have pointed out, UVA is actually a leader in integrating digital tools and techniques into teaching and research. Elijah Meeks, a digital humanities specialist at Stanford, praises UVA’s at once measured and innovative approach to the deployment of digital technologies in the humanities, and Vaidhyanathan details some of the successes. UVA professor Daniel Willingham wonders if Dragas et. al. are even slightly familiar with UVA’s leadership in this area.

Because I recently had a conversation with my university’s president that suggested he’s committed to getting this whole online education thing right at Boise State, I was surprised to see him publish a post on the UVA debacle titled “A Classic Case of Public Higher Education up against the Changing Educational Marketplace.” I’m taking the liberty of quoting the entire post:

Here’s the latest example of a public university’s governing board struggling with how to offer educational programming that meets the needs of students in our 21st century cyber world. Historically, the faculty have control of the curriculum, but it is becoming increasingly clear that new mechanisms of shared governance must be invented to assure that decisions are made in a timely fashion that respond to changing student demands and needs. Apparently, the University of Virginia President spent too much time justifying the status quo decision-making apparatus of the University and the Board sought new leadership with an urgency about how the University responds to its environment. Makes sense to me.

That sound you heard? My jaw unhinging.

I had also somehow missed President Kustra’s post on a similar theme from earlier in June. An excerpt:

Here we have a veteran faculty member in the UT College of Education going over to the “dark side” with the usual and predictable mention of the inability of UT to respond to moves like this given the cutbacks in higher education budgets in Texas. Could it be that the “dark side” is the “enlightened side”, unencumbered by traditions of faculty and department control of curriculum that has been known to slow things up when universities are responding to rapid changes in the marketplace and community of ideas?

I know it’s hard to recover when the wind is knocked out of you so thoroughly. Fellow faculty, I’ll give you a moment to catch your breath.

We’re fortunate, I think, to have faculty like Vaidhyanathan and Willingham willing to speak out about these issues, as well as folks like Jim Groom, Martha Burtis, Alan Levine, Audrey Watters, Bryan Alexander, George Siemens, Laura Blankenship, Barbara Ganley, Barbara Sawhill, D’Arcy Norman, Mills Kelly, Amanda French, Dave Cormier, Patrick Murray-John, and Gardner Campbell,*** all of whom have, over the past several years, written thoughtfully and passionately about the truly necessary revolutions in digital learning. Another champion for logic in online education is Colorado State University professor Jonathan Rees of More or Less Bunk, who has for many months been pointing out that the Emperor of Online Education has no clothes. Here’s an excerpt from a recent jeremiad:

How much experience in the classroom does Bill Gates have? How much experience in the classroom does Helen Dragas have? Come to think of it, how much experience in the classroom do most edtech entrepreneurs have? While I know a few computer science professors have gotten involved in these startups, what boggles my mind is the number of people basically fresh off the street who seem to think they’re education experts.

(Be sure to also check out Rees’s recent posts “Frankenstein’s Monster,” “Why Stay in College?,” and “Are College Professors Working Class?”)

There are so many naked emperors in education technology–and far too many college presidents, trustees, and politicians willing to compliment ed tech marketplace “leaders” on their fine new robes.

Although I rarely act on it these days because I’m too busy pursuing tenure****, I have a deep entrepreneurial streak–something that President Kustra and others seem to celebrate in faculty–and an abiding curiosity in how we can best use digital tools to help students develop as learners and citizens. Yet I’m loath to develop any kind of online course for Boise State in part because its intellectual property policy offers a major disincentive to doing so. The policy, published on the eCampus website, states that faculty don’t retain IP rights to their own courses:

A course (as a designed collection of assembled and authored material) produced under University sponsorship, where the University provides the specific authorization or supervision for the preparation of the course, is a work made for hire (as defined by law and Boise State policy). A course specially ordered or commissioned by the University and for which the University has agreed to specially compensate or provide other support (such as release time) to the creator(s) is a commissioned work, (as defined by Boise State policy). In either case, the copyright to the course will be held and exercised by the university.

Furthermore, faculty members must get permission to re-use their course material at other institutions:

The faculty author/developer retains the right to request permission from the university to use parts of the course or the course in its entirety at another institution or setting. Granting of permission will be at the exclusive and sole prerogative of the university.

It’s funny–I didn’t realize faculty duties added up to “work for hire” (neither does the AAUP) or “commissioned work.”

Still, it’s a bit simple to boil down my objections to online-education-as-usual to intellectual property concerns. In fact, I’m frustrated that faculty control of e-course IP has been the most-vocalized theme among my Boise State colleagues. Even if I found myself in a different institutional context, my primary objections to online courses would be more in line with Rees’s than with those whose misgivings about online ed are primarily related to copyright and remuneration.

See, the tools the university and ed tech entrepreneurs expect me to use—course management systems, lecture capture, and publishers’ digital “textbook” packages–are so ridiculously sub-par that I don’t know whether to laugh or scream. I’ve had several conversations with publishers’ reps where they insist on walking me through their online environments and showing me their extensive quiz interfaces even though I tell them that I don’t quiz students or expect them to know any of the “content” that’s covered in the publishers’ sample quizzes.

They just don’t get it.

One bright spot: The Academic Technologies folks at my institution do get it, as evidenced by the terrific mobile learning summer institute they hosted at the end of May. Still, mobile learning here is in limited release, and too many of the participants were more curious about the BlackBoard app than they were about what they could have their students create or discover with the slick new iPads we all were issued.

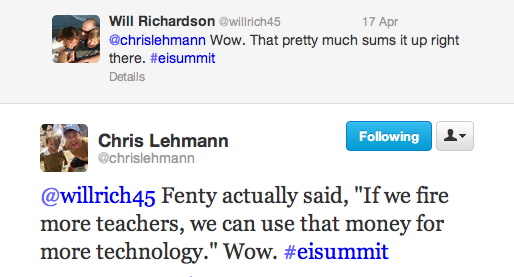

I’ve been fairly AWOL on this blog of late, and I certainly haven’t been writing as much about educational technology as I did in the old space, circa 2006 to 2010, when the bulk of my job description involved the intersection of pedagogy and technology and when I was presenting at conferences with the Fear 2.0 posse. Mostly I’ve been too disgusted to write about the “reforms” to Idaho education. I know I am sick of hearing “reformers” claim that we should fire teachers so we can provide students with more technology–as Audrey Watters points out happened at the Davos-esque Education Innovation Summit.

That said, it’s past time for me to heed Watters’s call for educators to call the bluff of entrepreneurs and uninformed, wealthy folks who want to reform the educational sandbox by melting it down for silicon. Writing of her absence from that summit, Watters says it most eloquently:

What I learned from the Education Innovation Summit is mostly something that I learned about myself (partly because I’ve learned already about a lot of this corporate ed-tech nastiness, sadly). I learned I have to maintain my presence at these events, even when the attendees make me angry or uncomfortable. I have to continue to “speak truth to power” when it comes to education and its future. I have to be a witness. I have to provide a record. I have to speak up and speak out. I can’t let my fury stop me from writing. I can’t worry about compromising myself by being at the places where the rich and powerful are at play with our collective future, because the greater compromise is to walk away and be silent. I think that’s probably what they want, after all.

As I’ve mentioned here a couple of times, I’ve been experimenting in my history classes with mobile technologies in particular, and I plan to write more about those experiments soon. I’m just now making sense of all the data I collected from my spring-semester students on their experiences with educational technology in my class and outside of it, and I will be applying to the IRB to expand this study to my other classes. I’m looking at how we can get students using these devices to “do history”–to investigate primary sources, compile data, document people and places, create platforms to disseminate their work, and engage with the public.

Yes, of course I believe technology can be used thoughtfully with undergraduates. I continue to approach new technologies with curiosity and a good deal of eagerness.

But ed tech entrepreneurs (and others) without classroom experience who are trying to reshape my students’ learning environments in ways that make absolutely no sense? I’m ready to go all Hans Christian Andersen on their asses.

—–

* And oh look, this site suggests it’s 6 percent.

** I’d love to have some more specific figures for you, but apparently my “supervisor” (whomever that may be) needs to submit a request for me to have access to reports in the university’s data warehouse. Unfortunately, since all my computers are Macs and I don’t use Internet Explorer or run a virtual PC, I can’t access that data anyway.

*** Major oversight on my part: I’m not reading enough on this subject written by people of color. Who do you recommend I read?

**** Which you’d never know from the tenor and content of this blog post, eh?

It’s almost the end of the semester here. I’m knee-deep, soon to be hip-deep, in grading. Wheeeeeeeee!

So, more good than bad. Yay.

How are things with you, dear readers?

Everyday life in Boise is similar to that of many of the places I’ve lived or visited. There are ridiculous numbers of big box stores and chain restaurants, late-1970s suburbs featuring ranch-aspiring homes of mediocre construction and design, sprawling new suburbs, a downtown that appears to be on the upswing, too many crappy supermarkets to count, a few historic buildings, a regional university, a couple dog parks, several commercial strips that appear to be caught in the 1970s, and some nice hiking in the hills on the edge of town.

As long as one doesn’t leave town much, it’s pretty easy to forget that Boise is more considerably more isolated geographically. In fact, it’s the most isolated city of its size in the United States; our nearest “big city” is 350 miles away–and it’s Salt Lake. Let me put it this way for my urban readers: if I want to make a Trader Joe’s run, I need to drive 320 miles to Bend, Oregon.

Even though its geographic isolation is significant, Boise is even more dramatically isolated politically from the rest of the state. That doesn’t mean the city is a hotbed of liberalism; I read someplace that about 30 percent of the students at Boise State are Mormon, and they tend to be politically more conservative than the average bear, and we have several active military and veteran students as well, and while I’ve found them to be more politically dynamic than the Mormon students, they are yet another reminder that I’m not in Davis anymore. (My sense is that students here are more likely to have fought in the oil wars than to bicycle against them.) Still, as long as I don’t pay too much attention to the news when the state legislature is in session, I can keep my blood pressure relatively stable, as politics in Boise itself are decidedly moderate.

Friday was an exception. Friday I was slapped hard by the realization that I moved to a very, very conservative state.

Idaho’s Human Rights Act protects people from employment and housing discrimination regardless of race, gender, or religion, but LGBT people in Idaho can be fired or refused housing because they’re gay or transgender. On Friday, a state senator, motivated by a group (and growing movement) called Add the Words, Idaho, proposed a bill to the State Affairs Committee to add sexual orientation and gender identity to the Human Rights Act. The Idaho Statesman relates what happened next:

In the committee’s narrow view, this proposal didn’t even merit real consideration. Friday’s hearing was a “print hearing” — when a committee decides whether to introduce a bill. A printed bill becomes a piece of the session’s public record — a document all Idahoans can read and judge for themselves.

Legislative committees sometimes print bills to advance the discussion of an important issue. On Friday, discrimination didn’t make the cut. The State Affairs Committee had neither the time nor the empathy. Committee members couldn’t dismiss this idea or its proponents quickly enough.

Idaho’s existing Human Rights Act bans employment and housing discrimination on the basis of race, religion or disability. The “Add The Words” bill would have added sexual orientation and gender identity. “There’s lots of groups who don’t have that ability as well, so the issue becomes, where does it stop? Where do those special categories end?” McGee asked.McGee said his constituents in Canyon County don’t support the change. He acknowledged that discrimination does occur against gays and lesbians in Idaho, saying, “For me to tell you that this doesn’t exist would be naive.” But, he said, “I think what we did today is say we don’t believe that this is the right way to deal with that.” Asked the right way, he said, “Continued education,” and added, “We say no to legislation all the time.”

Add the Words supporters told me that in conversations with individual senators, they have also been told that there just isn’t time this legislative hearing for such a bill.

That’s hilarious, considering the session I sat through on Friday lasted all of 55 minutes, and most of it was dedicated to apotheosizing Abraham Lincoln. There was time enough for not one but two Christian prayers, and for a lengthy reading of some things Lincoln said–including his opinion on banknotes. We heard, of course, about how he freed the slaves, but also about how he turned all his enemies into his friends. (Um. . . wasn’t he assassinated? Seriously–I wish the Senate would post the text of the prayer and readings on its website; it was a piece of ahistorical work if ever there was one.*) There was time enough for someone to sing “God Bless the U.S.A.”:

I’d thank my lucky stars,

to be livin here today.

’Cause the flag still stands for freedom,

and they can’t take that away.

I was choking on the irony.

There was once nice moment during the session, but I missed it because we were sitting at an angle that obscured our view of the senate president’s desk: Senator Nicole LeFavour of Boise, Idaho’s only openly gay state legislator, walked up to the dais and placed a sticky note on it. The note was a physical reminder of the thousands of sticky notes sent from all over the state and posted in the Capitol in support of Add the Words. LeFavour’s crossing into the well of the senate chamber was a serious breach of protocol, and it appeared to send some of the Republican senators into a confab in the senate antechamber. But what could they do? Censure the legislature’s only openly gay member on the day Republicans once again denied equal protection under the law to gays?

I’m a bigger fan than ever of LeFavour, who during the session also asked her fellow senators to recognize the Add the Words people in the gallery by applauding for us. It was an uncomfortable moment, I think, for everyone in the chamber and gallery.

I want to emphasize that, unlike in Washington state and California this week, the issue under consideration was not gay marriage, which was forbidden in Idaho by a state constitutional amendment in 2006. We’re talking about basic civil protections. Regardless of what Senator McGee believes, adding protections for LGBT people isn’t going to establish a slippery slope by which the state will be forced to add countless “special categories” of people to the act. This is a group of people who face significant discrimination and even physical danger in the state–discrimination that McGee himself recognized in the Spokesman Review article–and they need and deserve legal protection from discrimination and abuse.

I’ll be writing respectful letters to the senators on the State Affairs Committee, as well as to my own (Democratic) senator–who, based on what I heard from Add the Words leaders, has been lukewarm to the bill, even though he wrote me a note last month assuring me he supports it. As Senator McGee said, it’s clear Idahoans are in need of “continued education.” As an Idaho resident, historian, professor, and LGBT ally, I’m happy to provide such education to our legislators.**

One more thing. . . Would you pretty please “Like” the Add the Words page on Facebook? Every little bit of support is appreciated.

* If any historian is going to be OK with lay public interpretations of American history, it’s me. Seriously, I’m fascinated by such attempts to construct both hegemonic and alternative narratives. But in this case the irony was too big, the stakes too high.

** I’ll be even happier when federal laws extend full civil rights to LGBT folks, and I can write about how these Idaho senators were as much on the wrong side of history as those who opposed civil rights for women and people of color.

As promised, here’s another mini-rant, or rather series-of-questions-whose-answers-would-likely-lead-me-to-mega-rant. And with this one, I’d really like your assistance.

Because I’m one of only two faculty in my department whose specialty is officially “public history”—mind you, we all practice one form of it or another, but I have been anointed by my position description—pretty much all the applications for admission to our Master’s in Applied Historical Research program come across my desk. Usually I just write a few notes explaining why I’m recommending we admit the candidate, admit hir provisionally, or decline to admit hir, and then that’s the last I see of the application. I also don’t get to see my colleagues’ comments on the application, as that might unduly bias me.

Occasionally, however, an application comes back to me when individual faculty make conflicting recommendations about admission. So, for example, I might say we should admit someone, but two or three of my fellow faculty recommend the opposite. In many departments, a majority “no” vote might be the end of the line for an application, but our graduate program director gives me (or anyone else whose vote differs, I’m assuming) the opportunity to reconsider the application, to change my vote or take a stand or something in between.

At such moments, I get to see the admissions recommendations and, more importantly, the comments of my fellow evaluators. And often I’m in complete agreement with what they’re saying about the application, but I still want to recommend the opposite of what they do.

I’m not sure why, but it took me a year and a half in the department to realize that our occasionally differing visions about who should be admitted to the program stem from our–wait for it–differing visions about the program’s capabilities and mission.

My friends, we lack collective clarity.*

See, we have two programs: a traditional M.A. in history, and the M.A.H.R. The department’s web page describes the programs using almost exactly the same language, differentiating between the two only by saying the M.A. will prepare students for work in academic settings at all levels (by which I assume we mean high school teaching or the occasional adjunct gig) and the M.A.H.R. prepares students for careers outside academic settings. Programmatically, the degree requirements differ very little, with M.A.H.R. students taking one additional seminar in public history—but when I taught that course last spring, there were several M.A. students in it, too. The M.A.H.R. students can substitute “skills” courses (like GIS or video editing) for the foreign language courses required of the M.A. students. The M.A.H.R. students are also allowed, and encouraged, to take more internship credits.

If you’ve been around the history graduate program block lately, maybe you’re reading this as I do: the M.A.H.R. program is about helping students take very specific steps toward getting jobs. The M.A. program. . .maybe not so much. I don’t work with the M.A. students much, so I’m not sure what they want out of the program, but the M.A.H.R. students often have very specific goals: to open a historical consulting firm, to go into museum exhibit development, to make a documentary film, to apprentice themselves in a historic preservation office.

My latest (implied) rant took the form, then, of a memo to the graduate program coordinator in which I asked these questions (and provided my own tentative answers):

Here’s the thing: I read a lot of mediocre writing in those applications, from both M.A. and M.A.H.R. applicants. Many of the objections from my colleagues stem from applicants’ bad writing or poor research skills. And in my own classes, I’m a pretty unforgiving taskmaster when it comes to writing. So I’m not suggesting that we lower to the admissions bar for M.A.H.R. applicants. Yet maybe we need to acknowledge that public historians’ work embraces a huge spectrum; some public historians might find themselves addressing K-6 students, while others work primarily with policymakers. On the job, some will rarely write anything longer than an exhibit label. Others will need to write eloquently in grant proposals. Many will need to do both.

I suspect that many of the applicants who can’t write a good enough academic essay to be admitted to a traditional academic programs can still engage in critical and creative thought–it’s just that the essay isn’t the best way for them to exhibit these skills. Someone who is a good fit for our M.A. program might not be a good fit for the M.A.H.R. program, and vice versa. I suspect we faculty have been treating applicants as if they’re applying to the same program.

The grad program coordinator told me to bring my questions and concerns to the faculty at a department meeting. Our faculty meetings are relatively fleet things, thank goodness, but it also means I need to find a way to encourage people to either (a) coalesce around a unified vision in, oh, 10-15 minutes or (b) reflect on what they think the difference between the two programs should be and share their individual visions with me before the next meeting.

Of course, before I do that, I’d like some information from other programs. I’ll be scouring departmental web pages and perhaps contacting some folks, but in the meantime, here’s what I’d like from you, dear readers:

If you teach in, or pursued a degree within, a humanities or social science department that offers to graduate students an “academic” track and a “practical” or “non-academic career” track, how do you differentiate between applicants to the two programs? Do you require essays or something else? Do you require interviews? Do you expect applicants to propose specific projects? Do you ask recommenders to comment on the applicants’ career potential instead of just their academic performance? How can you tell which applicants might be a better fit for one degree track over another?

Please share your experiences in the comments. I know many of you maintain your anonymity on the interwebz, so you can either obfuscate a few details, comment anonymously, or you can e-mail me privately at trillwing -at- gmail -dot- com.

Many thanks!

* . . .in an academic department. A stunning revelation, I know.

Photo by vlasta2, and used under a Creative Commons license.

If you're looking for a good, ranty read, check out Fang's Forum.

© 2025 · WordPress