Six

Six

Fang has already written a paean to five. (And he totally stole my idea for a blog post, the bastard, and then did a far better job than I would have.)

Six years ago today (Labor Day–ha ha) at around 1:30 p.m., I finally delivered baby Lucas into the world. Forty-plus hours of labor produced a lovely but cranky baby boy who would, it ends up, not sleep through the night for fifteen months. Add his only-weekly bowel movements and colic, plus the thrush and mastitis that he caused in me, and you can begin to see why we stopped with just one child. (Another significant data point in that study: $50,000 in daycare and preschool costs over 5 years.)

Knowing how it all turned out, these six years later, if we had the financial werewithal and physical energy, we’d be jonesing for a sibling. Lucas is bright, inquisitive, funny, creative, and sensitive. He’d be an awesome big brother.

I am so very grateful that in the cosmic genetic lottery, we ended up with this child. I’m thrilled that Fang is his father, as he’s ensuring that the quirkier aspects of our joint DNA experiment are channeled productively in an environment filled with love, understanding, and creativity.

Congrats to all of us, then, on six.

Eighty-eight

Yesterday my mom and her sisters held a memorial for my grandmother, who died last month at age 88. Like many family weddings, it was in a backyard. Despite my grandmother’s assertion that everyone she knew was dead, 52 people showed up. We’re not a particularly religious family, but I imagine it was a service infused with tremendous spirit and gratitude.

I say “I imagine” because the memorial ended up being scheduled on the day between Lucas’s birthday party and his actual birthday, and I didn’t think it was appropriate to drag him to such an event on what should be an awesome, Lucas-focused weekend.

Still, my parents opted to read aloud some of Fang’s blog post from last spring, as well as the letter I wrote to my grandmother the week before she died. When my mom read the letter to my grandmother a month or so ago, Grandma apparently announced, with typical grandmotherly pride, that the letter needed to be framed and hung on the wall, as well as published in the newspaper. (Cute, yes?)

Anyway, I had thought the letter was the kind of thing that she’d want to keep private between us, but apparently she wanted it shouted to the world, so I’m going to share it here. If you’re family, get out the tissues. . .

Dear Grandma,

I know you’re going through a really bad time right now, and I wish I could do much more to help. The best I can think to do right now is to put in writing—so that you can read it, or have it read to you, more than once, if you like—how grateful I am to have you as my grandma.

I love you. You’re not only the best grandmother I could ask for, but also one of the best friends. I’ve been wandering around this world for 36 years now, and I’ve realized something:

Everyone else has old ladies for grandmothers.

I have you.

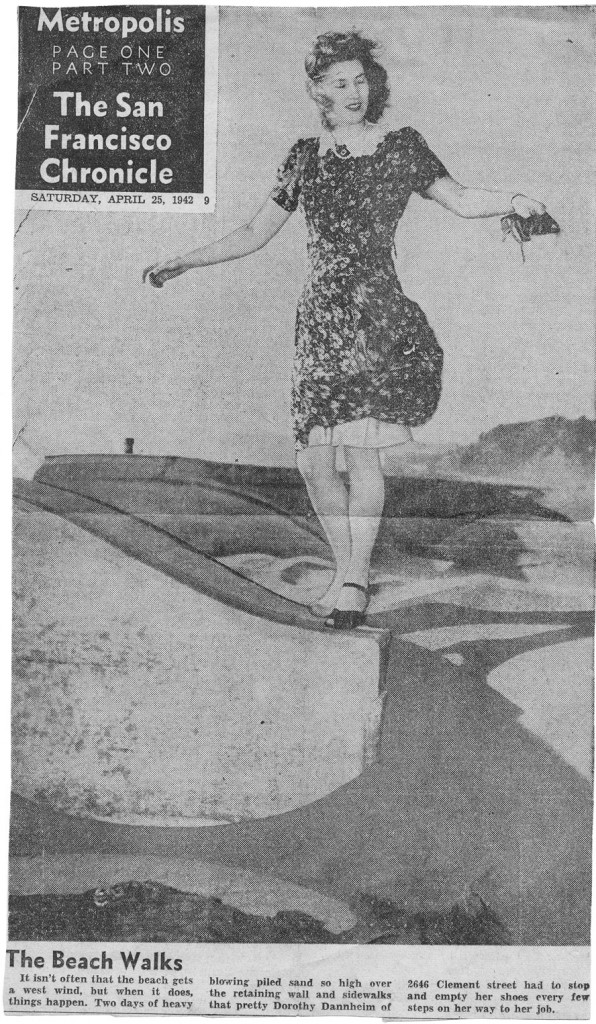

I have pinned up on my bulletin board at work the photo of you that was printed in the newspaper—the one where you’re emptying sand from your shoes. It makes me smile every day. I wish I could have known you then as well as now; how fun it would have been to be young together!

Regardless, I’m so happy for the time we’ve spent with each other. You have created an absolutely amazing family of women—daughters and granddaughters—dedicated to the public good through education. I’m so grateful to be a part of that clan, to be a recipient of that heritage. I’m so glad that Lucas feels he knows you well—he’s more [Surname 1] and [Surname 2] than you may know.

You contributed so much to my growth, not only by taking care of me before and after school, but also by letting me live with you for a time. I treasure all those memories.

Some things I remember:

- Making kites from dowels and white butcher and tissue paper on your kitchen table, and gluing onto them pictures of jewelry you helped me cut out of the J.C. Penney catalog. Pops and I flew the kites on the playground at Fremont.

- Thirty-six years of frosted and sprinkled sugar cookies. (It’s a miracle, really, I’m not diabetic.) I have your recipe, and I make the cookies with Lucas. He loves to add the sprinkles.

- Drawing portraits of each other while sitting at the old marble table in the living room. I was in elementary school. You drew a really funny, ugly picture and we both laughed really hard.

- How much you helped me with my tricky “Think Pages” while I sat at the big round table in the kitchen. They were really hard for a third grader, but it was fun to have you figure them out with me.

- When I once said a bad word, you told me you were going to wash my mouth out with soap, and then you asked, “Where’d you learn that crap?”

- You knew, somehow, that [Fang] was going to propose to me on my 26th birthday. I remember leaving your house for a fancy dinner, and you asking me, “What if he asks you to marry him?” I think of you several times each day when I look at the wedding ring you gave me. I still have the envelope in which you handed it to me, with the business card from the jewelry store.

- Looking for four-leaf, and even five-leaf, clovers under your lemon and grapefruit trees. One day we found six or seven of them. You taped them to pieces of notepaper, and we wrote the date on them.

The last time I was at your house, I went out into the yard and looked for four-leaf clovers, but there weren’t any. I wish I could send you a bouquet of them.

Mom told me you’ve been praying. I hope it’s helping you with all the awful things you’re going through. I was reading some poetry recently, and a few lines of a Walt Whitman poem jumped out at me, as it captured this idea, I think, that you’ll always, always be a part of this family, and of me especially:

We use you, and do not cast you aside—we plant you permanently within us;

We fathom you not—we love you—there is perfection in you also;

You furnish your parts toward eternity;

Great or small, you furnish your parts toward the soul.

You have definitely contributed to my soul, to the woman and mother I am today. Thank you for that. A million times thank you.

[Fang], Lucas, and I love you very much. Please know that we’re thinking of you all the time.

Love,

Leslie