I adore this video.

Random bullets of OMFG you’ve got to be kidding me

It’s almost the end of the semester here. I’m knee-deep, soon to be hip-deep, in grading. Wheeeeeeeee!

- I’m collaborating on a grant proposal. I recently took the lead on a small but significant part of the project. An organization with whom I thought it would make sense to collaborate just quoted me a price tag for their participation that is, oh, 9 to 15 times what I expected it to be. And these are people with whom I genuinely wanted to collaborate, in part to establish a long-term relationship that would be beneficial to us all. FML.

- Fortunately, I’ve found similar organizations that are willing to step into that breach, and for 1/3 the cost of what I expected to pay. Yay!

- My students are finishing up their 40-person group project, and I’m concluding this semester’s students-with-iPads experiment. I’ll have more to say about that, I’m sure, when I see the final product.

- The final product is going to require a bunch of technical work from me. It will test the limits of my WordPress knowledge, I suspect, but the PHP and CSS that don’t kill

memy site only make mestrongermore likely not to mess it all up in exactly the same way next time. - I also had an honest-to-goodness research question, with human subjects approval and everything, related to the mobile learning experiment this semester. More on that this summer, once I tally students’ responses to the surveys and card sorts.

- I remember there was a time when I was desperate for journal article ideas. Now I have more than I can write. It’s not a bad problem to have.

- I had two digital history interns this semester, and the work they’ve done has been really helpful to me and fun and useful for them. I have a little bit of summer money to throw their way, too, so they can continue with the project.

- I learned today from a reputable source that a key administrator thinks my plan to fully integrate digital humanities training into our public history M.A. program is solely a ploy to put “toys” (iPads) into faculty hands. Methinks a conversation is in order.

- I just had a really nice invitation extended to me from another key administrator. It’s nice to know my work with technology is being recognized around here.

- I’ve also had lots of warm fuzzies from students lately, in that way that only students can give compliments–you know, along the lines of “I fucking hate my other classes this semester. I wish I had you for all my classes because I enjoy our readings and discussions so much!”

- Today I signed off on an art student’s senior exhibition pieces. She did an awesome job, and she even referenced taxidermy. (She put me on her committee because we bonded over our fascination with human hair ornaments and taxidermy on the first day of my Women in the American West class this semester.) It was fun, too, to be on a committee with three art professors.

- In other news: sugar cravings are hard. I think I’ll be happier when the summer fruit arrives.

- That said, 11.5 days into my veganism, I’m not really missing dairy. I suspect I’ll go 30 days without refined sugar or artificial sugar substitutes, and then let myself have one treat each week. The vegan thing will likely last longer, though I may be a fair-weather vegan; I have a soft spot, for example, for parmesan cheese on pasta, and for buttercream cake frosting. (If you’re a vegan who has a fabulous substitute for such things, let me know.)

- I was doing this vegan and sugar thing to see how it would make me feel. A nice side effect? I’ve lost 9 pounds over the past week and a half.

- Tonight I had a pretty damn brilliant idea for an infographic/stunning visual image. It’s good that I’m married to a graphic artist. I hope we can bring the idea to fruition.

- I’m looking forward to summer. I have too many projects, and I need to try to remember to relax and enjoy my time with the boy.

So, more good than bad. Yay.

RBOC, that-time-of-the-semester, highly parenthetical edition

- Good god—it’s been more than two months since I last blogged.

- It’s that time of the semester. Paper deadlines and exams swoop down upon undergraduates. Students cry in my office and, quietly, at the back of my classroom—but not about the course. Even the usually-stoic-in-class veterans are teetering. One student veteran recently pointed out that his classmate, also a veteran, is much more, er, complicated than he is, though the latter student had only been to one war, and the former had been in two. (These are not UC Davis students, I am constantly reminded.)

- I, too, have deadlines galore. Maybe I need to have a good cry in my office. I suspect I’m teetering and haven’t yet recognized it. (I look around the unbelievable mess of my home office: yep, definitely teetering.)

- I decided, amidst all this deadlining, to give up sugar. (Those of you who have ever had a meal with me know to look out the window for pigs on the wing.)

- And then I thought, hell, why not give up dairy and eggs, too?

- It’s only day two of those experiments, but I already feel better. And for the hundredth time I cite the Seamus Heaney line: “You are fasted now, lightheaded, dangerous”—a great time to blog.

- My kindergartener is so awesome. And so is his dad. In fact, I suspect my kid is awesome in large part due to his dad.

- Fang’s fiftieth birthday is on Friday. How the hell am I married to a 50-year-old man? (And why do I look closer in age to 50 than Fang does? I must investigate the attic for a portrait.)

- Mostly I’m feeling overwhelmed with the little things at work. So many little things! But summer is coming, and the little things will, because they must, go poof!

- Big things, not so much with the poofing. I wrote a proposal to Academic Technologies to make our public history master’s degree the university’s “mobile learning” program, and (to, I think, the great disbelief of my colleagues) our department won that CFP. That project will come home to roost in a big way this summer.

- Our interim chair, who is literally counting down the days to the end of his year in that position, yesterday asked me if I was director of our public history program. Um, no. Regardless, he assigned me to speak as the director of said program when our accreditation visitors arrive next week. “Director” comes with more money, yes?

- I’m very much in absorption mode, an intellectual sponge. Reading, thinking, reading. Downloading articles. Jotting down notes. And then—miracle of miracles—messing around the edges of articles that need substantial revision. This is usually a sign that Big Writing is on the horizon. That’s good. Big Writing must get done.

How are things with you, dear readers?

Add the Words, Idaho

Everyday life in Boise is similar to that of many of the places I’ve lived or visited. There are ridiculous numbers of big box stores and chain restaurants, late-1970s suburbs featuring ranch-aspiring homes of mediocre construction and design, sprawling new suburbs, a downtown that appears to be on the upswing, too many crappy supermarkets to count, a few historic buildings, a regional university, a couple dog parks, several commercial strips that appear to be caught in the 1970s, and some nice hiking in the hills on the edge of town.

As long as one doesn’t leave town much, it’s pretty easy to forget that Boise is more considerably more isolated geographically. In fact, it’s the most isolated city of its size in the United States; our nearest “big city” is 350 miles away–and it’s Salt Lake. Let me put it this way for my urban readers: if I want to make a Trader Joe’s run, I need to drive 320 miles to Bend, Oregon.

Even though its geographic isolation is significant, Boise is even more dramatically isolated politically from the rest of the state. That doesn’t mean the city is a hotbed of liberalism; I read someplace that about 30 percent of the students at Boise State are Mormon, and they tend to be politically more conservative than the average bear, and we have several active military and veteran students as well, and while I’ve found them to be more politically dynamic than the Mormon students, they are yet another reminder that I’m not in Davis anymore. (My sense is that students here are more likely to have fought in the oil wars than to bicycle against them.) Still, as long as I don’t pay too much attention to the news when the state legislature is in session, I can keep my blood pressure relatively stable, as politics in Boise itself are decidedly moderate.

Friday was an exception. Friday I was slapped hard by the realization that I moved to a very, very conservative state.

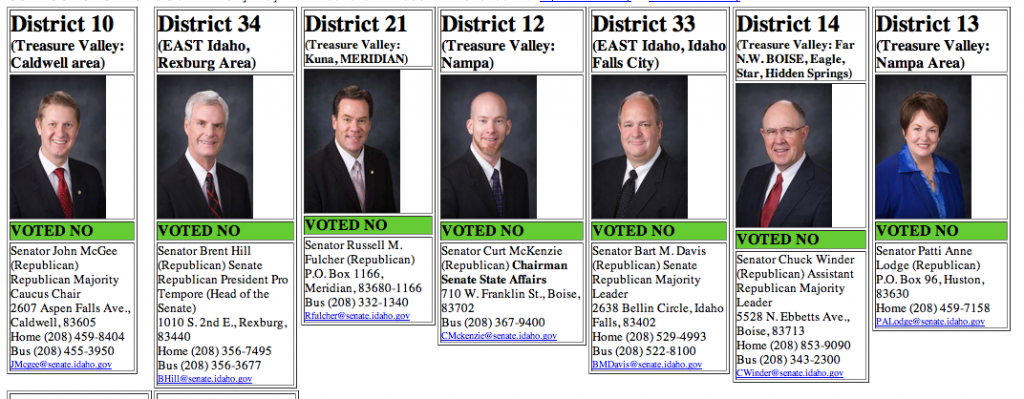

Idaho’s Human Rights Act protects people from employment and housing discrimination regardless of race, gender, or religion, but LGBT people in Idaho can be fired or refused housing because they’re gay or transgender. On Friday, a state senator, motivated by a group (and growing movement) called Add the Words, Idaho, proposed a bill to the State Affairs Committee to add sexual orientation and gender identity to the Human Rights Act. The Idaho Statesman relates what happened next:

In the committee’s narrow view, this proposal didn’t even merit real consideration. Friday’s hearing was a “print hearing” — when a committee decides whether to introduce a bill. A printed bill becomes a piece of the session’s public record — a document all Idahoans can read and judge for themselves.

Legislative committees sometimes print bills to advance the discussion of an important issue. On Friday, discrimination didn’t make the cut. The State Affairs Committee had neither the time nor the empathy. Committee members couldn’t dismiss this idea or its proponents quickly enough.

Idaho’s existing Human Rights Act bans employment and housing discrimination on the basis of race, religion or disability. The “Add The Words” bill would have added sexual orientation and gender identity. “There’s lots of groups who don’t have that ability as well, so the issue becomes, where does it stop? Where do those special categories end?” McGee asked.McGee said his constituents in Canyon County don’t support the change. He acknowledged that discrimination does occur against gays and lesbians in Idaho, saying, “For me to tell you that this doesn’t exist would be naive.” But, he said, “I think what we did today is say we don’t believe that this is the right way to deal with that.” Asked the right way, he said, “Continued education,” and added, “We say no to legislation all the time.”

Add the Words supporters told me that in conversations with individual senators, they have also been told that there just isn’t time this legislative hearing for such a bill.

That’s hilarious, considering the session I sat through on Friday lasted all of 55 minutes, and most of it was dedicated to apotheosizing Abraham Lincoln. There was time enough for not one but two Christian prayers, and for a lengthy reading of some things Lincoln said–including his opinion on banknotes. We heard, of course, about how he freed the slaves, but also about how he turned all his enemies into his friends. (Um. . . wasn’t he assassinated? Seriously–I wish the Senate would post the text of the prayer and readings on its website; it was a piece of ahistorical work if ever there was one.*) There was time enough for someone to sing “God Bless the U.S.A.”:

I’d thank my lucky stars,

to be livin here today.

’Cause the flag still stands for freedom,

and they can’t take that away.

I was choking on the irony.

There was once nice moment during the session, but I missed it because we were sitting at an angle that obscured our view of the senate president’s desk: Senator Nicole LeFavour of Boise, Idaho’s only openly gay state legislator, walked up to the dais and placed a sticky note on it. The note was a physical reminder of the thousands of sticky notes sent from all over the state and posted in the Capitol in support of Add the Words. LeFavour’s crossing into the well of the senate chamber was a serious breach of protocol, and it appeared to send some of the Republican senators into a confab in the senate antechamber. But what could they do? Censure the legislature’s only openly gay member on the day Republicans once again denied equal protection under the law to gays?

I’m a bigger fan than ever of LeFavour, who during the session also asked her fellow senators to recognize the Add the Words people in the gallery by applauding for us. It was an uncomfortable moment, I think, for everyone in the chamber and gallery.

I want to emphasize that, unlike in Washington state and California this week, the issue under consideration was not gay marriage, which was forbidden in Idaho by a state constitutional amendment in 2006. We’re talking about basic civil protections. Regardless of what Senator McGee believes, adding protections for LGBT people isn’t going to establish a slippery slope by which the state will be forced to add countless “special categories” of people to the act. This is a group of people who face significant discrimination and even physical danger in the state–discrimination that McGee himself recognized in the Spokesman Review article–and they need and deserve legal protection from discrimination and abuse.

I’ll be writing respectful letters to the senators on the State Affairs Committee, as well as to my own (Democratic) senator–who, based on what I heard from Add the Words leaders, has been lukewarm to the bill, even though he wrote me a note last month assuring me he supports it. As Senator McGee said, it’s clear Idahoans are in need of “continued education.” As an Idaho resident, historian, professor, and LGBT ally, I’m happy to provide such education to our legislators.**

One more thing. . . Would you pretty please “Like” the Add the Words page on Facebook? Every little bit of support is appreciated.

* If any historian is going to be OK with lay public interpretations of American history, it’s me. Seriously, I’m fascinated by such attempts to construct both hegemonic and alternative narratives. But in this case the irony was too big, the stakes too high.

** I’ll be even happier when federal laws extend full civil rights to LGBT folks, and I can write about how these Idaho senators were as much on the wrong side of history as those who opposed civil rights for women and people of color.

All manifestoed out, part I

I was just reading about how young Assistant Professor Newt Gingrich was booted from his History department and dumped unceremoniously on Geography because he was thinking too much about the future for a professor of history. I fear I may be coming across as a bit Gingrinchy this week, as I just realized it’s only Wednesday and I’ve already written three mini-rants about the future directions of the department and university.*

I’m going to share versions of them here, as each really raises more questions than it answers, and I know my wise and worldly readers may have some wisdom to share in the comments.

Rant the first: On teaching and learning with technology

A senior colleague said The Powers That Be were looking to completely remake the university’s ways of teaching undergraduates within six years, and that this revolution would be brought to us by online courses delivered (I suspect) through Everyone’s Favorite Learning Management System. Online courses, it was suggested, would automagically improve the university’s ridiculously dismal graduation rates.

I couldn’t help but put on my Critical Thinking Cap** and ask these questions:

*To be fair, all three were solicited, rather than imposed in a fit of manic delusion.

**Yes, humanists–even those of us with cultural studies degrees–do have access to such things.

Because we don’t already have enough to do or worry about

The boy has become an even bigger target for bullies, and it has moved into physical altercation territory. Fang explains.

Feel free to return here to The Clutter Museum to offer suggestions based on your own experiences as a child or parent. Your stories and solutions are appreciated!

Image by Barnaby Wasson, and used under a Creative Commons license

Ice Cube salutes the Eames

Although I very much appreciate his comments on the character of L.A. freeways, my fave moment comes at 1:46.

An experiment in online course evaluation

Back when I was in the cube farm of academic technology, we tried an experiment within our then-new course management system: we had a large class (hundreds upon hundreds of students) pilot a mid-semester evaluation. The instructor emphasized the importance of the evaluation and reminded students to take it, but our return rate was still only 8 percent. It pretty much soured me on online evaluations, as such a low return rate renders the evals useless. (At UC Davis at the time, veterinary students did get an invitation to chat with the dean personally if they didn’t fill out their course evals. Otherwise, there wasn’t any institutional effort to “incentivize”* students–that is, the registrar wouldn’t withhold a student’s grades until she had filled out her course evals.)

Fast forward to today. Boise State is offering online course evaluations, but recently the university announced that whether or not a course participates is not up to the instructor; each department either has to stick with in-class, paper-based evaluations or go all in with the online evals. In the department meeting where we discussed the issue, we were leaning toward paper, and then one colleague said he had piloted online evals and was getting response rates of 90 percent. I’d like to see the evidence of that, but whatever. . . it was persuasive enough that the sense of the meeting shifted toward a semester trial of online evaluations.

We’ve been told we should “incentivize” student participation in online evaluations, for example by offering perks (e.g. students could bring a 3″ x 5″ note card with them to the final exam or we’d drop the lowest quiz grade) if the class return rate reached, say, 80 percent. And yes–those are the actual suggestions from the administration. Never mind that I don’t give quizzes, and my students already can bring essay outlines on notecards to the final–I’m not going to reward students for doing something that I see as part of fulfilling the social and intellectual contract for the course.

So instead of offering to bribe my survey students, I spent an entire class talking (as I often do, but this time more frankly and comprehensively) about why I’ve taught History 111–U.S. history to 1877–the way I have.

Topics covered, and student reactions to each one:

- memories of high school history, what they learned, and what they’ve used since then: mostly not good, dates and events, and not much, respectively.

- experiences with, and feelings about, lectures in college, regardless of discipline: mostly bad, crappy PowerPoint presentations; suspicions that a professor or two is bullshitting them full-time.

- political versus social and cultural history: prior to college, students haven’t been exposed, by and large, to social and cultural histories, except in very small amounts; they find it refreshing, particularly if we’re doing “history from below.”

- students as vessels to be filled with “content”** and the relation of this approach to online courses and pedagogies of scale: resentment, boredom, disbelief.

- survey textbooks***: expensive, unreadable, useless–pretty much unadulterated loathing.

Our conversation lasted 45 minutes, and at the end I made another pitch for them to fill out course evaluations, saying that their feedback is not only valuable to me individually, but it also allows instructors to make a case to deans and provosts and beyond that customers students do think about learning in ways that should matter to us. I then reiterated to them that I really do make changes in my course structure and teaching style based on student feedback, and that since I may have 30 more years (!!!!) in the classroom, they have the opportunity to make a big impact on future students’ learning experiences. I encouraged them to take ten minutes or so to fill out the evaluation as soon as possible.

This class’s online response rate thus far, more than halfway through the response window? Twenty-one percent. Anyone care to guess how little that number will rise, even with repeated urgings, by the time the survey closes on Friday evening? Leave your bets in the comments.

* Worst word ever? Possibly.

** Remember when we used to say “knowledge” instead of “content”?

*** For the record, I used Major Problems in American History, Volume I by Elizabeth Cobbs Hoffman et. al.; Abraham in Arms by Ann Little; Mongrel Nation by Clarence Walker; and They Saw the Elephant by Joann Levy. Each book takes a very different approach to history, with Little’s being the most traditional (yet also very readable!), Walker’s serving as a witty and searing examination of why different American demographic groups view the Jefferson-Hemings liaison in divergent ways, Levy’s book offering thematic chapters but not footnotes or endnotes, and Major Problems bringing together eight to ten primary sources in each chapter with two essays usually excerpted from books by academic historians. My students found Little’s book challenging at first but conceded they enjoyed each chapter more than the previous ones. Walker’s book was puzzling but made for the best class discussion because it was the most explicitly provocative. Levy’s book was the most accessible, and my Idaho students seemed to appreciate its focus on western women’s history, as their exposure to regional women’s history (or, actually, any women’s history) previously was via pioneer wives and Sacajawea. I suspect most students stopped reading the essays in Major Problems as early as a third of the way into the semester, and many students needed a great deal of guidance in interpreting primary sources.

Whiteboard image by Skye Christensen, and used under a Creative Commons license.

Public history Ryan Gosling

As a follow-up to Feminist Ryan Gosling, someone has created Public History Ryan Gosling.

What others are saying about recent events at UC Davis

I’ve been following pretty closely the response to the pepper spraying at UC Davis, and I’ve been hoping to find time to blog about it. Unfortunately, between grant writing and grant reviewing and end-of-semester craziness, I haven’t had time to share or comment on the 75 or so tabs I have open in Firefox at the moment. Those tabs are really beginning to slow down my laptop, so I thought I’d clear out some of them by sharing some of the more interesting tidbits.

Close readings

Lambert Strether offers a play-by-play description and transcription of the most popularized video of the incident.

Lili Loufbourow undertakes a close reading of one of the videos of the pepper spraying. Here’s an excerpt:

It’s transcendently brilliant, this tactic–the students offer an alternative in a high-pressure situation, a situation that no one wants, but which seems inevitable in the heat of the moment. It’s an act of mercy which, like all acts of mercy, is entirely undeserved. Watch the other officers’ surprise at this turn in the students’ rhetoric, after they had (rightfully) been chanting “Shame on you!” Watch the officers seriously consider (and eventually accept) the students’ offer.

As the officer in the left foreground teeters back and forth, nervous, braced, thinking, watch the power-drunk cop on the right (who I think is the one who pepper-sprayed the crowd earlier) brandish not one but TWO bottles of pepper-spray, shaking them, not just in preparation, but in anticipation. He’s seconds away from spraying the students again. His mask is up, you can see his face, but it’s a nonexperience: it’s blank, immobile. It would be inaccurate to say that he’s immune to the students’ appeal; he’s not even bothering to listen. All he hears are sounds. No signals, all noise.

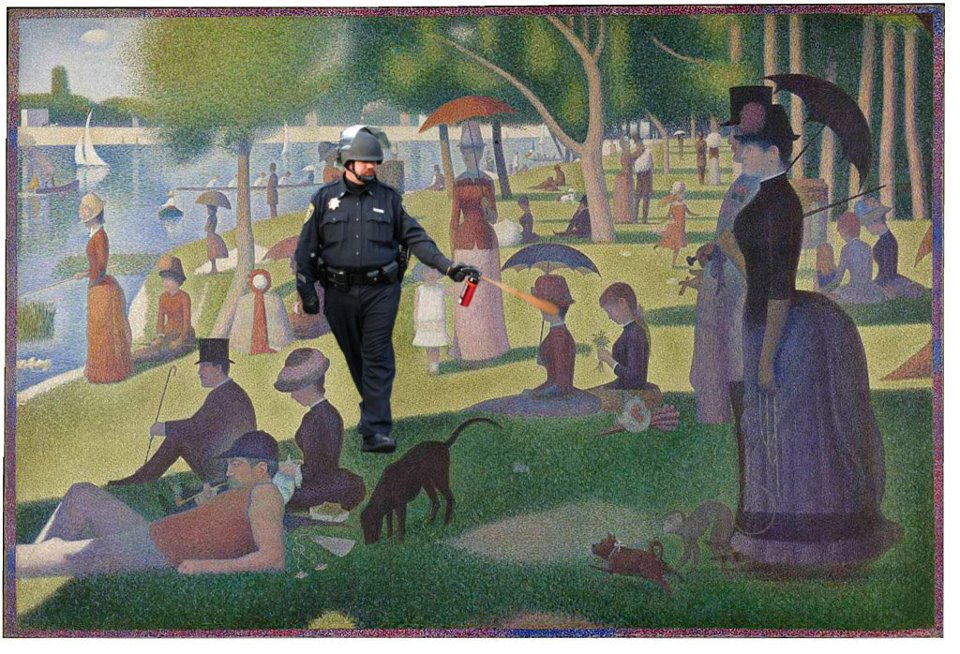

Megan Garber suggests that the image of the pepper-spraying cop could change the trajectory of the Occupy movement:

The image itself, I think — as a singular artifact that took different shapes — contributed to that transition, in large part because the photo’s narrative is built into its imagery. It depicts not just a scene, but a story. It requires of viewers very little background knowledge; even more significantly, it requires of them very few political convictions, save for the blanket assumption that justice, somehow, means fairness. The human drama the photo lays bare — the powerless being exploited by the powerful — has a universality that makes its particularities (geographical location, political context) all but irrelevant. There’s video of the scene, too, and it is horrific in its own way — but it’s the still image, so easily readable, so easily Photoshoppable, that’s become the overnight icon. It’s the image that offers, in trending topic terms, a spike — a rupture, an irregularity, a breach of normalcy. It’s the image that demands, in trending topic terms, attention.

And it also demands participation.

Hence we have an entire blog devoted to the meme of the Pepper-Spraying Cop. Here’s a sample image:

(Speaking of memes, check out the reviews on a pepper-spray canister at Amazon. This one is my favorite.)

(Speaking of memes, check out the reviews on a pepper-spray canister at Amazon. This one is my favorite.)

Gen Y on Occupy UC Davis

BoingBoing has an interview with one of the students who was pepper sprayed. The student provides a concise summary of what the students are protesting at Davis:

We’d been protesting at UC Davis for the last week. On Tuesday there was a rally organized by some faculty members in response to the brutality on the UC Berkeley campus, and in response to the proposed 81% tuition hike.

One of the reasons I am involved with #OWS, and advocating for an occupy movement on the UC campus, is to fight privatization and austerity in the UC system, and fight rising tuition costs. I think that citizens have the right to get an education regardless of economic condition. Most people are not going to get a job where they can afford to pay off student loans. But to exclude people from knowledge is unconscionable.

Zack Whittaker comments on UC Davis Police Chief Annette Spicuzza’s explanation for the pepper spraying—“Officers were forced to use pepper spray when students surrounded them. . .There was no way out of the circle.” Yet everyone who had seen the videos of the pepper spraying could see that Lt. John Pike stepped over the protestors to spray them in the face. Whittaker uses this failure of police department and university spin as emblematic of the new era of citizen journalism. While I hesitate to call most of the witness-created media from the UC Davis protest “citizen journalism”—much as I’m loath to call this round-up of UC Davis links “curation”—Whittaker does have a point about how Generation Y experiences flashpoints:

What we see in any modern event, no matter how off the cuff or sporadic, is a sea of cameras. One report likened it to a panopticon society.

It is not 911 or 999 we call in an emergency. We do not think to engage with the situation. But what we do, as the Generation Y, is pull out our phones and start recording; documenting every second of the event for history’s benefit.

Responses from UC Davis faculty

As far as I know, the first letter-length response from a faculty member at UC Davis came from Nathan Brown, an assistant professor in the English department, who called for UC Davis Chancellor Linda Katehi’s resignation.

Because it’s been well publicized, if you’ve been following this event at all, you’ve probably already seen music and technocultural studies professor Bob Ostertag’s editorial on the militarization of campus police. (I was Bob’s TA when I started the original Clutter Museum, and if you ever have a chance to hear him speak, I recommend you seize it.) I want to highlight a couple of passages. First, Ostertag considers the use of pepper spray as both a health concern and disciplinary measure:

I just spoke with a doctor who works for the California Department of Corrections, who participated in a recent review of the medical literature on pepper spray for the CDC. They concluded that the medical consequences of pepper spray are poorly understood but involve serious health risk. As with chili peppers, some people tolerate pepper spray well, while others have extreme reactions. It is not known why this is the case. As a result, if a doctor sees pepper spray used in a prison, he or she is required to file a written report. And regulations prohibit the use of pepper spray on inmates in all circumstances other than the immediate threat of violence. If a prisoner is seated, by definition the use of pepper spray is prohibited. Any prison guard who used pepper spray on a seated prisoner would face immediate disciplinary review for the use of excessive force. Even in the case of a prison riot in which inmates use extreme violence, once a prisoner sits down he or she is not considered to be an imminent threat. And if prison guards go into a situation where the use of pepper spray is considered likely, they are required to have medical personnel nearby to treat the victims of the chemical agent.

(How hot is the pepper spray UC Davis police used? Check out Deborah Blum’s post for the science of pepper spray.)

Ostertag also provides, very briefly, a history of linked arms in civil rights protests in the United States. He then explains how the meaning of linked arms has shifted:

Throughout my life I have seen, and sometimes participated in, peaceful civil disobedience in which sitting and linking arms was understood by citizens as a posture that indicates, in the clearest possible way available, protestors’ intent to be non-violent. . . . Likewise, for over 30 years I have seen police universally understand this gesture. . . .

No more.

The UC Davis English department is calling for the resignation of UC Davis Chancellor Linda Katehi—on the department’s home page. The department also asks for the disbanding of the University of California police department. The Physics faculty also has released a letter calling for Katehi’s resignation.

Professor Emeritus Jon Wagner offers a flyer for “UCD Omni-Spray: A Broad Spectrum Democraticide” (PDF).

Cynthia Carter Ching has issued an apology to students and encouraged her fellow faculty to recommit themselves to administrivia, even though such work is neither interesting nor fulfilling:

And in many cases that power wasn’t just taken from us, we gave it away, all too gladly.

You know, it wasn’t malicious. We thought it would be fine, better even. We’d handle the teaching and the research, and we’d have administrators in charge of administrative things. But it’s not fine. It’s so completely not fine. There’s a sickening sort of clarity that comes from seeing, on the chemically burned faces of our students, how obviously it’s not fine.

So, to all of you, my students, I’m so sorry. I’m sorry we didn’t protect you. And I’m sorry we left the wrong people in charge.

On the Monday following the Friday pepper spraying, the UC Davis community held a rally that attracted a couple thousand people (pic). The Sacramento Bee covered the events, and the Davis Enterprise reported on faculty who participated in the rally.

This week, UC Davis faculty are offering classes in a week-long teach-in. Were I still at UC Davis, I’d definitely be attending several of them.

Yudof has appointed former Los Angeles Police Department Chief William Bratton to lead the investigation of the pepper spraying incident. The women and gender studies faculty at UC Davis has launched a petition protesting that decision, with a very thorough and, I think, convincing explanation of why Bratton is not a good choice in this case. You can read their letter, and sign the petition if you’d like, at Change.org.

The bigger context

Kate Bowles at Music for Deckchairs suggests we need to look beyond Lt. Pike and investigate instead the forces that allowed his actions to emerge:

The world’s attention has been focused on the face and demeanour (and now the salary) of Officer Pike, wielding the pepper spray like a bug gun, but what brought each of his colleagues to that point where their collective and individual efforts in that awful situation felt appropriate, inevitable, even wise? How did each of them get caught up in this profound miscalculation, suddenly and so decisively on the wrong side of our global, chanting crowd?

Several columnists at The Atlantic chimed in as well. Alexis Madrigal picked up on Bowles’s theme with her post “Why I Feel Bad for the Pepper-Spraying Policeman, Lt. John Pike”:

Structures, in the sociological sense, constrain human agency. And for that reason, I see John Pike as a casualty of the system, too. Our police forces have enshrined a paradigm of protest policing that turns local cops into paramilitary forces. Let’s not pretend that Pike is an independent bad actor. Too many incidents around the country attest to the widespread deployment of these tactics. If we vilify Pike, we let the institutions off way too easy.

James Fallows considers the moral power of images emerging from the UC Davis protests and in another post highlights the callousness of the pepper spraying:

Watch that first minute and think how we’d react if we saw it coming from some riot-control unit in China, or in Syria. The calm of the officer who walks up and in a leisurely way pepper-sprays unarmed and passive people right in the face? We’d think: this is what happens when authority is unaccountable and has lost any sense of human connection to a subject population. That’s what I think here.

Also at The Atlantic, Garance Franke-Ruta offers a round-up of videos of violent police crackdowns against the Occupy protests. Ta-Nehisi Coates asks us to place the pepper spraying in a broader cultural context:

Not to diminish what happened at UC Davis, but it’s worth considering what happens in poor neighborhoods and prisons, far from the cameras. I’m not saying that to diminish this video in anyway. But I’d like people to see this a part of a broad systemic attitude we’ve adopted as a country toward law enforcement. There’s a direct line from this officer invoking his privilege to brutalize these students, and an officer invoking his privilege to detain Henry Louis Gates for sassing him.

Leadership

Cathy Davidson calls the pepper spraying a “Gettysburg Address moment,” in that “moral authority and moral force needs to be eloquently articulated before this historical moment devolves into violence and polarization.” She asks college presidents nationwide to demonstrate wisdom, passion, and moral vision.

University of California system President Mark Yudof issued a response to the pepper spraying. In response to his letter, Lili Loufbourow offers what is, in my opinion, the best-titled post on the whole clusterfuck: “Dear Mark Yudof: The Cemetery You Manage Can Hear You.” (The reference is to Yudof’s quip to the New York Times that “being president of the University of California is like being manager of a cemetery: there are many people under you, but no one is listening.”) Loufbourow gives us a blow-by-blow analysis of UC administration response to incidents at Berkeley and Davis–it’s worth a read, but if you work for the UC or a similar system, be sure you take your blood pressure meds first. See also the e-mail messages from UC Berkeley Chancellor Robert Birgeneau et. al. to see in even more detail how the rhetorical sausage gets made.

Sherry Lansing, the chair of the UC Regents, released a carefully scripted and unpersuasive video statement. In a complete monotone, she declares, “We Regents share your passion and your conviction for the University of California.” To demonstrate the Regents’ dedication to the UC community, they’re opening up their next teleconference meeting to public comment for a whole hour. How generous!

Katehi

It ends up UC Davis Chancellor Katehi is one of the authors of a recent report recommending the end of university asylum in Greece. Niiiiice.

Here’s Katehi leaving a press conference and being greeted by a phalanx of students, faculty, and staff that was, by some estimates, 1,000 people strong:

She is accompanied by the campus chaplain, Rev. Kristin Stoneking, who wrote a moving post on why she walked Chancellor Katehi from the press conference.

I’m so proud of UC Davis students right now. For once I say this without sarcasm: Stay classy.