We’re into week five of my Women in America: The Western Experience course, which means it’s time for students to start to get serious about the final project. Since some Clutter Museum readers showed interest in how the project progresses, I thought I’d provide an update.

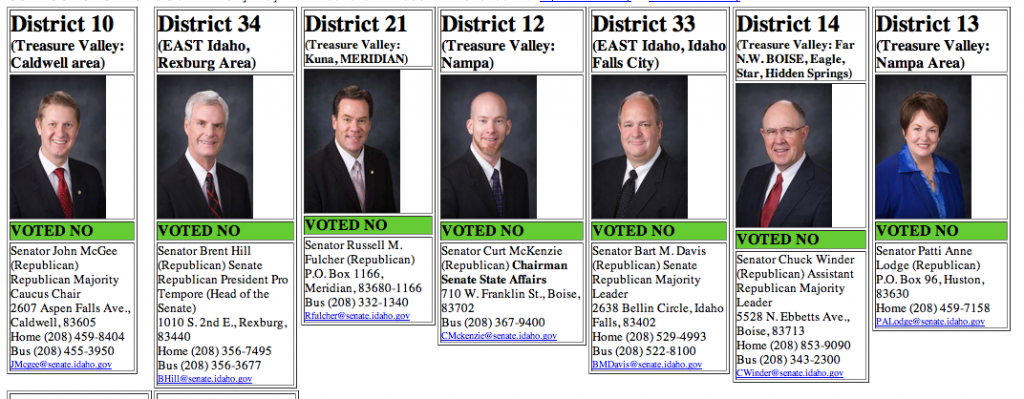

To review: my 40 undergraduates will be building an online exhibition about the history of Idaho women’s amateur arts and crafts. I’m leaving the platform open, but I suspect the choice will come down to WordPress or Omeka, and I’m guessing the students will choose WordPress, though who knows? Maybe they’ll surprise me. Because all the students in the course have iPads, I’m encouraging them to optimize the exhibit for that screen size and resolution.

Yesterday, student groups picked their topics from a list of arts and crafts categories, all of which are represented by artifacts in storage at the local museum:

- basketry

- wedding dresses

- lacework

- plein air painting

- beadwork

- taxidermy

- ornaments and wreaths made from human hair

- quilts

- needlework

There are eight groups, but I put nine possible topics on the list so that the final group to select a category still could choose between two of them. I can’t believe no one opted to study the Victorian human hair ornaments. I mean, seriously–one of the artifacts available for study and interpretation is a family tree made from intricately woven hair from each represented family member. What’s not to love?

Taxidermy was the last topic picked. The group seemed a bit disappointed in its topic, so I shared a bit of history with them, and now they’re pretty excited about it. Women + 19th-century U.S. + taxidermy = awesome wackiness. And god only knows what they’re going to find in the equation of women + 20th-century Idaho + taxidermy. I’m hoping for some steampunk.

Students will be heading to the museum to photograph artifacts on display there, and to museum storage to photograph and research additional objects. The museum’s curatorial registrar came to talk to the class yesterday about her job, the basics of artifact conservation, guidelines for photographing objects on exhibit, and the rules for viewing the artifacts in storage and using photographs of them online. She emphasized that, because of security concerns, the first rule of Museum Storage Club is that you do not talk about Museum Storage on social media or post photos of it or disclose its location. Students found that secrecy fascinating, I think.

Her talk definitely heightened some students’ sense of adventure in the project. Honestly, I’ve never seen anyone, and certainly not twentysomething undergrad, so excited to go try to photograph scraps of 100-year-old lacework in a dimly lit environment. I’m hoping they maintain this excitement throughout the semester. I’ll keep you posted. . .