Someone recently asked me what my greatest achievement has been, and my answer, without hesitation, was family. I’m lucky to have come from a ridiculously functional extended family, as there I learned many of the lessons I’ve applied in my own marriage to Fang. In just about any marriage, the challenges facing one spouse become the challenges of both, and Fang and I have spent many years challenging one another in inventive ways. Injuries! Illness! Big medical bills! Schedule changes! Depression! Relocation! Pay cuts!

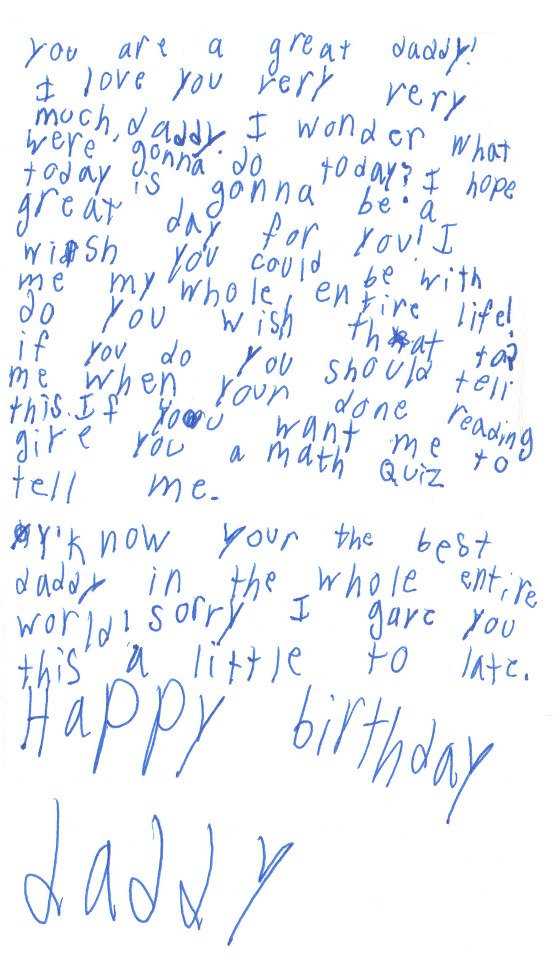

And yet we persevere. And we’re raising a damn fine kid, too, who somehow seems to have inherited the best of each of us. Even mainstream kids are not simple to raise, however–look back at the first year of this blog and watch us age a decade–and I’m proud of the results of our efforts. Fang in particular is an amazing father; in many ways he vibrates at the same frequency as the boy. They understand each other at a level that’s not always open to me. And while I’m jealous of that connection, I’m also grateful it exists.

I’m so glad we’ve made it this far together, and I look forward to our next adventures.

Happy eleventh anniversary, Sweetie.

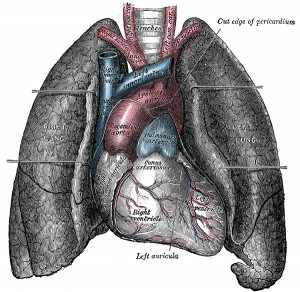

Today I was prescribed a third round of antibiotics for pneumonia. Anyone want to place bets on how functional I’ll be when classes begin on January 22? Or when I need to get back to working on some key collaborations on Monday?

Today I was prescribed a third round of antibiotics for pneumonia. Anyone want to place bets on how functional I’ll be when classes begin on January 22? Or when I need to get back to working on some key collaborations on Monday?