I am so thankful for my little family this week. Lucas has been a great gofer and has (mostly) kept himself entertained. (He has been making Valentine’s Day cards for the extended family and sewing little felt pouches adorned with hearts as gifts.) And Fang has gone above and beyond the requirements of those in-sickness-and-in-health vows he took a decade ago.

He has taken me to urgent care twice, fetched escalating prescriptions of antibiotics, fixed meals for the boy, kept Lucas entertained with reading and guitar lessons and movies, and more–all while meeting the multiple deadlines of a newspaperman (his preferred title). I am so very fortunate to have such a caring, thoughtful, capable spouse–especially since I suspect he knew the job wouldn’t be easy when he signed up for it.

Thanks so much, Sweetie. Here’s to a healthier new year!

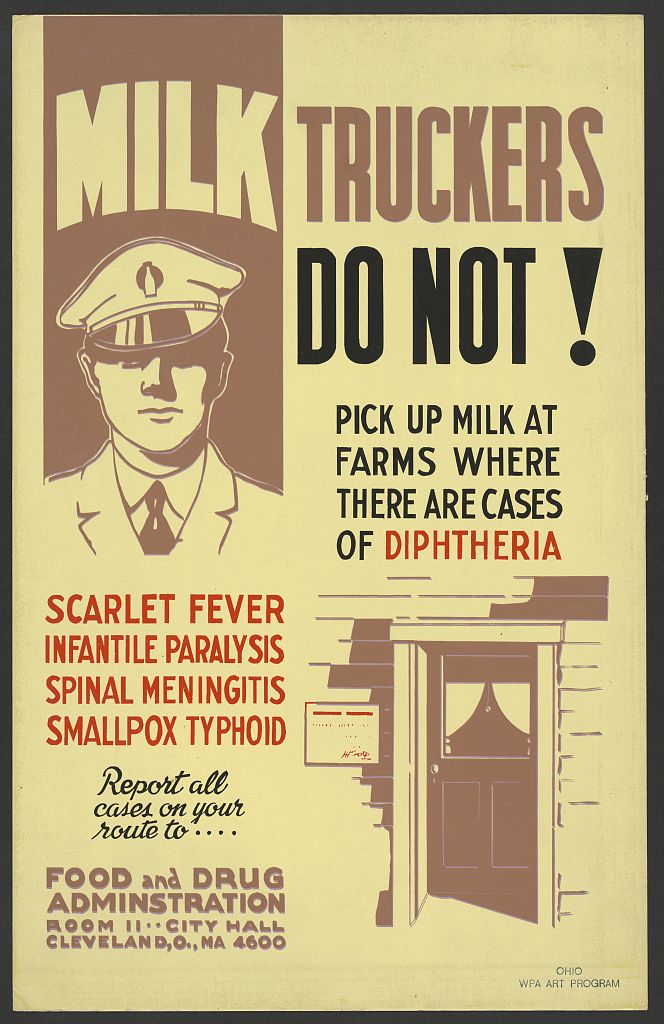

* “Milk Truckers” is one of my fave WPA posters of all time. Glad I finally found an excuse to use it.